YEOJA wanted to highlight some of the participants who we feel our community will be interested…

Sarnt Utamachote

An interview with the Southeast Asian queer filmmaker and curator3 August 2021

We recently sat down with Sarnt Utamachote, a Southeast Asian queer film maker and curator, whose work primarily focuses on the Thai diasporic community, to talk about their involvement with Non Native Native Fair 2021, their work, what it means to create in predominantly western white spaces, and the Thai Diasporic community:

Hey Sarnt! We understand that you are a filmmaker and curator. Can you tell us more about your work both creating films and curating them?

Sarnt: I had a dream to become a filmmaker since University (back in Bangkok), so I decided to move to Europe to study filmmaking. Long story short: everything sort of failed – I never got accepted to any film school and I ended up learning everything on my own. To earn a bit of money on the side, I started/got a chance to work in event management. I later realized event management is a form of “curating” (but less critical etc.).

Curating officially started for me after I launched un.thai.tled collective. Ultimately I think filmmaking and curating are similar; the person chooses, thinks, plans, works with, and – very importantly – cares for the subjects that will be represented, shown, and discussed. In both disciplines, I’m fascinated by the topics of diaspora, in-between-ness, the healing yet sometimes destructive power of marginalised communities, narratives from Southeast Asia (both in geography and in memory), mental health, subculture, and music. I describe myself/my work as “realist optimism” – I do not believe in overly-positive thinking/glorification of something, but I believe in positive confrontation and process of change and learning.

Do you have a personal favourite film maker who has influenced your work?

Sarnt: Of course I do, but rather than giving credit to established/canonized filmmakers (such as Andrei Tarkovsky, Theo Angelopoulos, Raya Martin, and Anocha Suwichakornpong), I prefer to give credit to the communities/circles of friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and kin that surround me. They are the ones that literally taught me and influenced my works dearly.

From Berlin Asian Film Network, BIPOC Film Society, Queer Media Society to Kino Loop; from queer-drug positive parties at Cafe Futuro, Ziegrastrasse, and even to the Thai Park community, these people taught me how and allowed me to position myself in this local economy, which is progressing towards each activists’ own version of ideal society. Both filmmaking and curating requires this symbiosis and isn’t mere “individual expression”; one needs to carry on (one’s life) with the stories passed on, heard, and gathered from others around them.

Video installation “Complicated Happiness” by Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Photo by Benjamaporn Rattanaraungdetch

Your curatorial work recently took the form of a cultural exhibition, “Beyond the Kitchen: Stories from the Thai Park” (2020). Can you tell us more about this exhibition? What the experience was like for yourself and the other artists who participated and how did the public/audience receive the exhibition?

Sarnt: This project initially started off by being a research group, run by Nut Srisuwan, Tanade Amornpiyalerk, Rosalia Namsai Engchuan, and Itirit Hatairatana (who later became one of the artists in this group exhibition). I joined in later, after the district museum Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf was looking for a “curator” for this project. Katrin Peters-Klaphake, my co-curator, really taught and guided me a lot, due to me having less experience with “curating” (but more [experience] with “event management”). Being a partially cultural and partially political project, on one hand we focused on the history of Thai diaspora in Germany (which I continued working on through my own project, archive), and on the other hand, we looked at the politics of informal migrant space.

Unfortunately due to capitalisation of exoticness and migrant labour, the district [museum Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf] still decided to “formalise” it -at this current moment (mid 2021) the project is in the process of internal discussion between bureaucrats and Thai community members. It felt really great to confront the bureaucrats and being part of re-writing and adding onto a predominantly white urban history. We didn’t really perform “Thainess” but, for the first time, publicly acknowledged its [the Thai diasporic community in Berlin] long-history and its position as “in-between”, neither Thai nor European.

Unfortunately due to the first wave of COVID-pandemic (February 2020), the public programme had to be cancelled and many things we planned couldn’t be realised. We did the best to welcome some (very) limited audiences in July of 2020, who were mostly happy (especially Thai-Germans) that someone finally critically researched, recognised, and archived the complexity of the Thai Diasporic space – beyond its “kitchen”.

What has it been like working in an industry predominantly run by cishet white men, how has your personal work been received by the mainstream film community vs. the queer and BIPOC community, and why is it so important that we have members from marginalised communities with intersecting identities in curatorial and leadership positions?

Sarnt: As I mentioned earlier, I made films for, even imagined/dreamt films up for particular communities I’m affiliated with – the intersection between queer/BIPOC (or Asian)/migrant positions. Yet at the same time, I do not expect them to well “receive” everything I do, nor do I glorify and think all BIPOC/queer persons will 100% understand what I do. Ultimately each [person] has different life paths and sets of knowledge (and most of the time different opinions).

I recognise the pain and abuse many of us (marginalised groups) created against each other, yet I do believe in “common struggle” and “common positions”, about which intersectionality taught us, if ever – the line between radical empathy and critical thinking. It’s important therefore to involve all of us in [curatorial and leadership positions], as due to “lessons learnt”, so we might be able to create our own perhaps fairer and better “sector” where the cultural makers meet the demands of audiences – hopefully – with less tendency for colonial-imperialism, sexism, and other forms of oppression.

Furthermore it’s important to involve each of us with our each-own complexity, so that we can develop multiple safe spaces. One size does not fit all. Having many different spaces with different goals is much better than having a few with the same goal. Without the queer/BIPOC/migrant community, I would have no audience, for whom I make the films or curate events for.

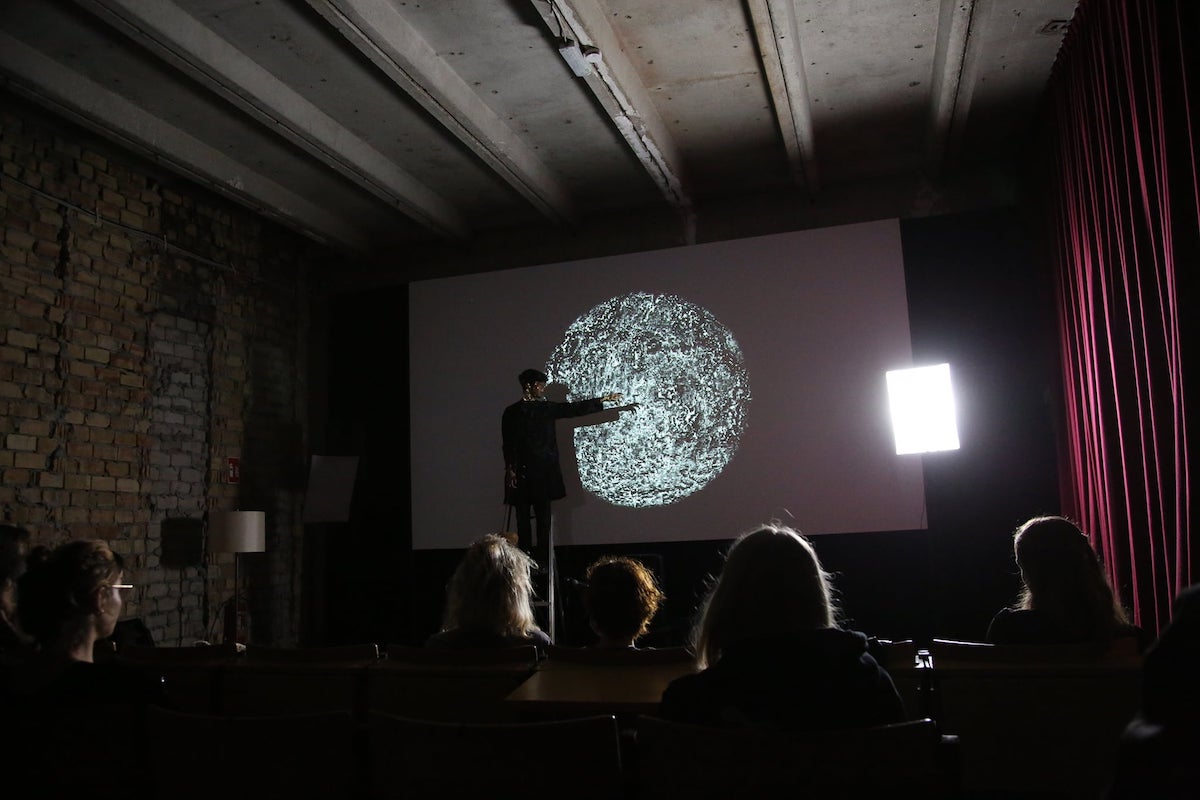

Part of un.thai.tled Film Festival 2020 at Sinema Transtopia/bi’bak

photography: Vanessa Macedo

You are also the co-founder of “un.thai.tled”, a collective for Thai-German critical creatives. Can you tell us more about the collective, what the collective’s goals are, and how it came about?

Sarnt: We hung out as group of friends first: myself, Wisanu Phu-artdun, Natthapong Samakkaew, Eily Thams, Chalida Asawakanjanakit, Kantatach Kijtikhun, Nicha Boonyawairote, Wong Echo, Theerawat Klangjareonchai, and Preeyawan Maneerat. We then later realised we could try to establish ourselves in the Berlin cultural landscape

However, we do not see ourselves as representatives of Thailand. This has always been the crucial point to us, that we take “Thainess” way way less seriously (we did even a “fabricated” “post-modern” Buddhist-inspired ceremony for our launch by near-end of 2019 at Chalet, Hermannplatz) and [see it] more as a challenge, as something to experiment with.

There are times we have performed “Thai-ness” from time to time in an “exotic” manner, for example performing traditional “Thai” music means we can earn a little money. But when possible, we work very very critically against royalist-nationalist narratives of Thailand as a “long-standing non-colonised” nation or “the land of smiles and peace. These are oriental/colonial constructions.

So far our goals are to raise visibility about our (Southeast Asian mainland) narratives and to create platforms for creatives in exile or in diaspora. Activism is important to us, although it remains a “part-time” job.We have had crossovers with the Thai Democratic People of Germany, the network of anti-government Thai exilants, and tried to stop the formalization process of Thai Park, which we sadly partially failed to accomplish due to the COVID-pandemic and district’s “non-transparency” regarding this.

Photo Series “Molt into me” by Kantatach Kijtikhun

Photography: Sarnt Utamachote

How has the asian diasporic community in Germany responded to your work?

Sarnt: Regardless of what “Asian” means, bi’bak, Korientation, Deutsche Asiatinnen Make Noise, Asian Performance Art Lab, Berlin Asian Film Network, Thai Students Association in Germany, Soydivision (Indonesian collective in diaspora; our partner in this Non Native Native Fair project), and even Thai migrant restaurants I have befriended, all have been very very kind and supportive of me. They are always the audiences I wait for and discuss with, who have no pre-judgement nor even question the validity of our [the Thai community’s] struggle. They represent not “Asianness” but a form of radical empathy, openness, and understanding – this is activism for me; I believe society could change, if we start the change on an interpersonal/private level.

This year, you took part in Non Native Native Fair, an experimental hybrid event that brings creative cultural practitioners together to present and sell their work, products, and labour in an online trade fair environment. How did you get involved and what was this experience like for you?

Sarnt: I got to know Non Native Native after I launched un.thai.tled via facebook, not because the founders of NNN are Thai but because their mission looks similar to few organisations in Berlin. I then met them physically at Darunee Terdtoontaveedej’s exhibition “Sacred Beings” at International Film Festival Rotterdam 2020 (in which my video installation, “I Am Not Your Mother” was exhibited) and we decided we need to do a crossover Germany-Netherlands project- due to long-standing historical links between the two countries (from both colonial times up until the Second World War) and the large population of Asian diasporas (with different colonial/migrational paths) in both places.

I want to thank Rosalia Namsai Engchuan (my usual curatorial partner-in-crime in Berlin who had to leave the project due to a tight schedule) who wrote the funding application and shaped the core concept together with us.

This experience felt great, with very non-hierarchical organisation However, it would have been much better if I would have had a chance to travel to Rotterdam, or they could have travelled to Germany. This project is not only about expanding the [Asian diasporic] network but about affirming “you aren’t alone.” Our common struggle takes place on a much larger scale than what we thought. This coincides with another project we did with Asian Art Activism London on the collective workbook for Asian* organisations in Europe called “Tools To Transform” (May 2021) and with global demonstrations against anti-Asian racism. This is exactly what I hope for in the future – transnational dialogues and archives of commonness across national borders in the European Union.

photography: Sarnt Utamachote

All of the work that you do centers predominantly around your identity as a Thai-German diasporic person and Asian diasporic communities at large. What made you decide to focus your work around the Asian diasporic experience?

Sarnt: Again it was the process I went through during the whole of 2018 of asking myself: “Am I Asian?” This word is so complex (in both positive and negative ways), yet I had been refusing to confront it the whole time. One only becomes “Asian” once one enters the white western world. I acknowledge strong colourism and racial-ethnic dominance is present within Asia).

The word “diaspora,” which I discovered in 2019, gave me a certain answer to this phenomenon once I added it after the word “Asian.” The Asian Diaspora directly intersects with the word “queer/non-binary” that has also been a part of me. Diaspora/Queer doesn’t concern only the assigned-at-birth aspects (which family-heritage or geography one was born into, which body or gender), but the possibility of change, of being in between, of questioning the binary/polar opposite visions of the world. Focusing on Asian diasporic experiences (especially in German contexts – beyond American narratives – although we have learnt so much from them) has great creative and historical potential. We are looking at a long-heritage of shameful colonial and imperial narratives, of solidarity across racial and gender lines for social justice, and at a fight against forced assimilation.

Where can readers watch your films?

Sarnt: Check the section “Filmography” on my website. Some videos are readily available online, due to their status as commissioned works (belonging to third parties), and some are still in the film festival circuit, which I are not currently available online – feel free to email me if you are interested in any of the films. Feel free to curate my film(s) for you festival or exhibition too!

Lastly, what projects and plans do you have for the rest of 2021?

Sarnt: I have affiliated myself with the organisation bi’bak/Sinema Transtopia since 2020, where I curated a few film programmes there. Imaginging Queer Bandung takes place from the 23rd of June until the 21st of August and features open-air film screenings, film-, and podcasting workshops for queer BIPOCs at Sinema Transtopia, Haus der Statistik/bi’bak. This queer BIPOC-focused programme is co-curated with filmmaker Popo Fan and community-worker Ragil Huda (representative of Queer Asia in Germany).

Near the end of the year, I will have another film programme there with a focus on the Southeast Asian mainland on the topics of anti-communist oppression during the Cold War. Apart from this, I’m shooting a short documentary film “Sonic Reverbs” (working title), which focuses on healing power of music and queer mental health. We are also hoping that Non Native Native Fair 2022 can be physically possible here in Berlin. Of course if my visa allows me to stay! (lol).

_

Original photography by Rae Tilly, exclusively for YEOJA Mag. To follow Sarnt on Instagram, click here. For Sarnt’s official website, click here. For more interviews, click here.