The British chapter was first proposed by Ghanaian analyst Akyaaba Addai-Sebo in 1987 and has…

Kara Walker’s Great Responsibility

on "Fons Americanus" & The Tate's Colonial History11 December 2019

London is a city in constant celebration of itself. Its memorials to people and events mark many important street corners and squares, they decorate parks and are in themselves, landmarks.

On the steps at the end of King Charles Street, not far from St James’s Park, stands a memorial to Robert Clive. He is immortalised in military regalia, holding a sword in his left hand. The bronze reliefs on the north, south and east faces of the plinth atop which he strides depict battles waged in the name of the British East India Company. In the instance of this sculpture, Clive, whose actions alongside Warren Hastings are credited as catalysing what would in the next century become British India, is considered a hero.

If you were to walk through the park, along Horse Guards Road before bearing right onto The Mall, you would be greeted by another bronze figure in the image of James Cook. Cook, who is remembered as a naval officer and cartographer (more presumptuously, as an ‘explorer’ rather than imperialist), made three voyages to the Pacific in Britain’s name. These journeys and the maps they produced became central to the subsequent colonisation of the region at European hands.

Clive and Cook—two of many of their kind—stand poised and casual. Their gazes are smug and unflappable—almost facetious—as we continue to celebrate them in death. Quite literally larger-than-life, they preside over a city whose riches were gained by way of exploitation both men can be directly attributed to. Theirs are but a small portion of the legacies we are expected to honour, rather than contest, nevertheless, they stand architecturally, their stone and bronze bodies existing as a part of the city.

“Insurrection! (Our Tools Were Rudimentary, Yet We Pressed On)” 2000

Cut paper and projection on wall

Photo: Ellen Labenski

© Kara Walker

Kara Walker first saw the Queen Victoria Memorial from the window of a taxi. The California-born multidisciplinary artist was on her way to Heathrow Airport, having just been commissioned to produce the Tate Modern’s annual Turbine Hall installation. This memorial (about fifteen minutes walk down The Mall from those of Clive and Cook) remembers Queen Victoria, the first Empress of India, who sits among a cohort of figures—Courage, Truth, Justice, to name a few—in marble and guilt. The sculptural group, which was dedicated in 1911, remains one of the city’s more iconic memorials. “I hadn’t even seen it before” recalled the artist in conversation with The New York Time’s Siddhartha Mitter. Walker took the image of her encounter with Victoria back to her Brooklyn studio.

Walker is best known for producing figures reminiscent of the image of the Antebellum South. It is typical of her work to consider race, oppression, and labour. Her large-scale installations consider the American psyche (or distinct lack thereof). They are, as artworks, inherently decolonial, though it is her point of considering the very nature of her materials and the buildings in which they are to be housed that renders her installations both uncanny and brilliant.

From May through July 2014, Walter installed A Subtlety (also known as the Marvelous Sugar Baby) in the disused Domino Sugar Factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The sculptural group was dominated by a central figure, a huge alabaster-white rendition of a woman, an older, black woman, a “Mammy” figure who lies on her forearms, like a Sphinx, nude but for a scrap of fabric tied around her head. She is turgid, unfeminine and unmoveable, so candidly evoking Hattie McDaniel’s eponymous character from her Oscar-winning performance in Gone With the Wind (1939). Eighty tonnes of bleached sugar were used to form Mammy the Sphinx, and she is watched upon by “attendants,” fifteen would-be decorative readymade blackamoors. In the factory, it became an installation of figurative irony. “The sphinx crouches in a position that’s regal and yet totemic of subjugation—she is ‘beat down’ but standing.” wrote Hilton Als in The New Yorker.

Unlike those working in the sugar factory native to its time, those terrorised by Clive and Cook, or those presided over by Queen Victoria, Walker—a modern American—is able to view monuments and buildings as sites of irony, and through considering them with the temporal advantage of retrospect, produce great art. As she is confined to her ability to only operate in the present, Walker looks back, unto what once was, producing as a result, seemingly ahistorical work.

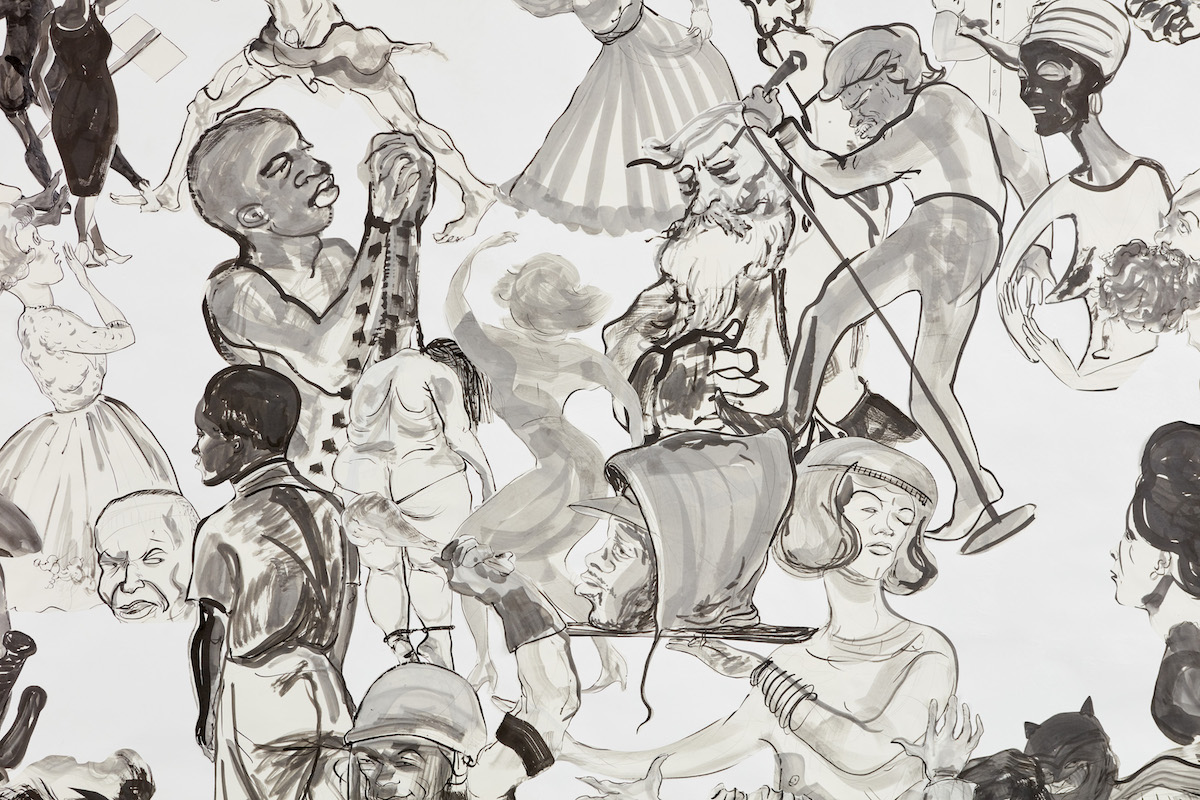

Detail from “Christ’s Entry into Journalism” 2017

Sumi ink and collage on paper

© Kara Walker

On the factory, Als continued: “Now the factory is about to be torn down and its site developed, and its history will be eradicated by apartments and bodies that do not know the labour and history and death that came before its moneyed hope.” In installing her work in a building with such a history, Walker was able to ask unanswered and ignored questions. Als writes, “Who cut the sugar cane? Who ground it down to syrup? Who bleached it? Who sacked it?” We must also ask: why has this responsibility—a decolonial responsibility—fallen on the shoulders of Black artists? When did it become Walker’s responsibility to consolidate the history of the sugar factory, as it would become hers to do the same in the Tate Modern?

I sometimes wonder what Walker would have produced, had her taxi driver not taken her on the scenic route to Heathrow. Her work Fons Americanus, currently being shown in the Tate Modern, deconstructs the memorial she passed quickly with adept brutality. When one enters the Turbine Hall from the large opening on the west side of the building, you hear a trickle of water, among the voices of the institution’s visitors. We are greeted by the precursory element of the installation sculpture.

It is an oyster’s shell when standing before it, one recognises that where the pearl should sit emerges instead of the face of a child. Tears pour from the jagged sockets of his eyes, and across his face is etched an expression of sheer urgency. When one continues past the child in the shell, you are then confronted by the main element of the installation. The fountain central to Fons Americanus (“the Fountain of America”) functions as an anti-sculpture, an anti-monument. It stands thirteen metres tall in an exercise of glorious neo-Victorian kitsch and with shocking white, evidently “made” figures, holds a mirror up to the monuments which decorate the London’s streets.

On the pediment—the middle part of the fountain, just above the pools—a figure modelled after Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian revolutionary sits comfortably. He is the central element of the monument, he occupies Victoria’s own seat, recalling the level of her importance as the face of an Empire. An overthrown slave owner grovels to L’Ouverture’s right, and to his left stands an inelegant tree bare of leaves. A noose hangs from its stubby branches. The figures preside over the chaotic scene in the water below. In the shallow two-tiered pools, a doomed woman swims away from thrashing sharks, in front of her, a shirtless man struggles in vain to regain control of his capsizing boat. Walker’s installation, which opened the public early in October this year and will be on view until April 5 2020, is allegorical of the history of the relationship between enslaved West Africans and water (the Atlantic). It is intelligent and sardonic, and completely necessary.

“Fons Americanus” 2019

Photography: Ben Fisher

© Tate

The crowning figure of the fountain will be remembered as one of art history’s great Venuses. It recalls so clearly the 1801 propaganda artwork, The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies. This duplicitous rendition of Venus depicts a Black woman attended to by cherubs as she stands poised in an oyster shell, she grasps at reins harnessed to two mythical sea creatures, who carry her across the ocean. The shell she stands on so proudly recalls that which houses Walker’s weeping child.

Sable Venus depicts the crossing from Angola to the Caribbean as not only willing but enjoyable, re-appropriating the image divine femininity immortalised in Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485-6), casting the Black woman as an idle, unwitting object to be used and desired. Walker’s Venus stands too, but with a distinct lack of grace. Though her arms are thrown up in exaltation, her stance is more precarious than celebratory. Water spurts freely from her exposed breasts into the pools below, recalling the gendered exploitation of enslaved women. A third current splashes onto the drowning figures metres below—the water pours from an open gash in Venus’ neck, and so her blood and milk nourish the chaos below.

When I gaze up at Kara’s Venus, at her mortal wound and writhing body, I think again of the triumphant golden figure atop the Queen Victoria Memorial across the river. What we know today as the Tate Modern opened in January 2000, after the high-profile renovation of the iconic disused power station. It is one of the country’s most visited art galleries, attracting 5.8 million visitors in 2018, nevertheless, few make the association between Tate the man and Tate & Lyle sugar—it wasn’t even until August of this year that the gallery released this statement, a preliminary examination of their benefactor’s direct, damning connections to transatlantic slavery.

The lack of engagement with the subject in light of Walker’s opening urges me to wonder whether it was a strategic PR move, whether Tate deems Walker’s commission and a conveniently timed statement enough to absolve their guilt as beneficiaries of the system their chosen artist has dedicated many of her works to lambasting. pomp and circumstance of its existence, also that of both memorials to Cook and Clive are suddenly rendered violent, more so than ignorant in the face of Walker’s suffering characters. It seemed that the streets of London are scattered with the products of trickle-down colonialism. It can be recognised as an act of violence to ascribe glory to the memory of evil individuals, but as Walker always makes sure to ask, what about the building?

“Fons Americanus” detail 2019

Photography: Ben Fisher

© Tate

Kara Walker did her job as an artist. Her anti-monument implores one to think twice about the many frivolous dedications which mark London. Fons Americanus can only be successful if the commissioning institution—the Tate group—acknowledge their own history as a postcolonial entity which, unlike the sugar factory, is far from defunct; it’s thriving. The gallery, which was founded in 1897 as the National Gallery of British Art took the name of benefactor, art collector and sugar magnate Henry Tate when they rebranded in 1932 to include a collection of modern art.

I would wager that many of the 130,000 visitors to the sugar factory in Brooklyn were in part interested by the finality of the occasion. A Subtlety (2014) could only exist then and there, seeing as the asbestos-ridden shell of a building was condemned to be torn down. There was no glory in it for the building. On the occasion of that installation, the factory was merely an auxiliary character.

In the instance of Fons Americanus, the power held by the building, by the Turbine Hall, is all too evident. Money still flows in and through the walls of the institution (and its three sister galleries), and there will be more to be made. When viewing Fons Americanus, I thought of the memorial in front of Buckingham Palace I’d seen so many times. I thought again of Clive and Cook, and I thought of the many times I’d paid to engage with art at the Tate.

Walker’s haemorrhaging Venus reminds us simply to question the skeletons of colonialism—the buildings and monuments, not just the people—and to read and question cities as we would a history textbook. Again, I must ask: why does this responsibility fall on Kara Walker’s shoulders?

_

Photography courtesy of Kara Walker and The Tate. For more articles on art + culture, check out our recommendations for 10 postcolonial texts to read by writers of colour.