The official Women's March website states: "The mission of Women’s March is to harness the political power of…

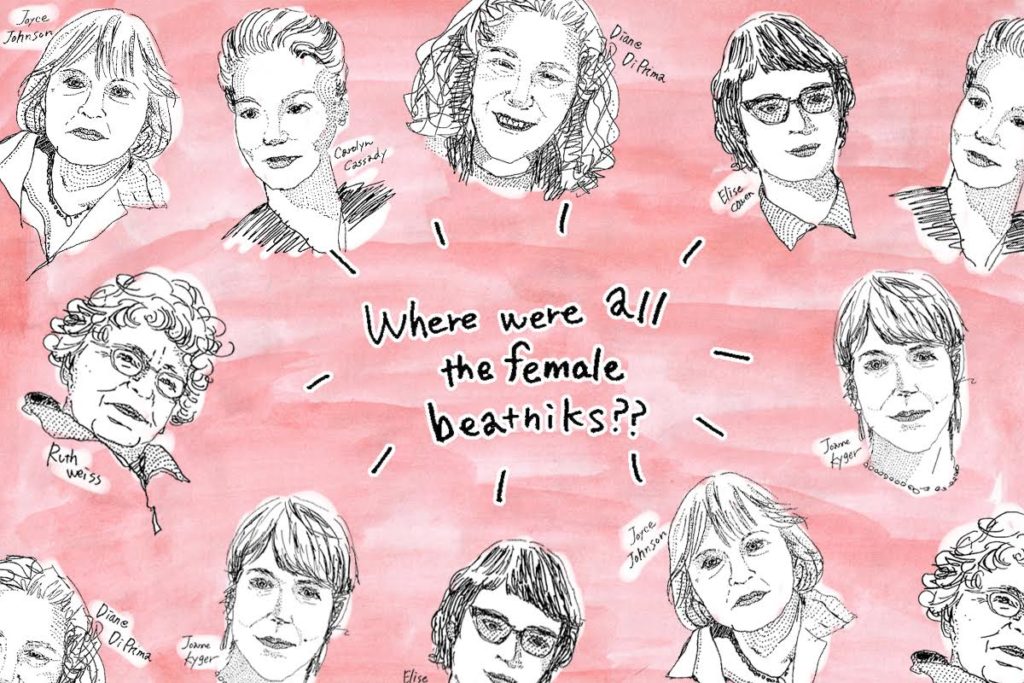

Where Were All The Female Beatniks?

12 April 2018

During the post-war 1940’s and 50’s, when poodle skirts, matinee icon hairstyles and wholesome family values were the norm, one silhouette stood out from the crowd. Slimline trousers and polonecks were stuck to skinny bodies, sunglasses and berets perched atop messy hair, and cigarette smoke blurred the sharp lines and angles of their figures.

They were the Beatniks – America’s mid-century counter-culture movement – and they were far more than a bunch of moody fashionistas. At their core were a group of young creatives who would change the face of literature forever.

When we talk about the Beat writers, most of us can only pull up three names – Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. The three are considered to be the cornerstones of the Beat revolution, and for good reason – Kerouac’s On The Road, Ginsberg’s poem Howl and Burroughs’s Naked Lunch caused controversy across the U.S and turned the publishing world on its head thanks to their depictions of rebellion, extreme drink and drug abuse, male relationships, and homosexuality.

“It was a time when people were casting off the shackles of conformity,” says David Wills, editor of Beatdom magazine. “People were ready to say “no” to censorship and outdated social norms, and the Beats really led the way.”

Their work was raw, and unhinged, and undoubtedly groundbreaking. However, the bohemian counterculture they fostered wasn’t quite as progressive as it seems.

“I try to block out certain aspects of the Beat movement because it was so misogynistic,” says the young woman in glasses behind the counter at the City Lights bookstore in San Francisco – the place that first published and sold many of the Beat masterpieces. She’s been studying the work of the Beats for a while, she tells me, but hasn’t quite managed to reconcile her interest in the movement with its anti-women undercurrent. “It makes me uncomfortable.”

The Beat boys, it seems, were determined to push boundaries but remained stubbornly old-fashioned in their views on gender. A select few women like Joan Vollmer – the sharp-witted wife of Billy Burroughs who was killed by a shot to the head when a drunken game of William Tell went wrong – were accepted wholeheartedly into the fold on account of their high intellect. For the most part, though, the girls were ignored and pushed aside, despite the fact that many were acclaimed authors and poets in their own right.

“The men didn’t really view the women as that talented,” says Wills. “They were loved and, to some extent, respected, but there was definitely an overall sexist mentality that said the men were creative geniuses and the women not so much.”

The 1940’s and early 50’s, when Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs were kickstarting the Beat revolution and developing some of their most iconic works, was an especially dry period for female voices in general. A woman’s primary function was considered to be as a homemaker and caregiver, and any deviation from that prescribed path was frowned upon by family, friends and authority. Girls from middle-class backgrounds were encouraged to go to college, sure, but career prospects were minimal. A good marriage and well-kept home remained the end goal.

Most of the women in the Beat scene at that time were college educated (or had at least spent a few months at school before dropping out). However, they were positioned within the group mostly as friends and lovers, and the way they were treated by both the Beat men and society at large explains why many of them had a hard time breaking out and showcasing – or even finishing – their own work. Some, like Carolyn Cassady and Edie Parker, only published their memoirs years later (and even then they were always considered passive observers of the male Beat ‘greats’ rather than as creatives in their own right). Joyce Johnson, a woman usually hailed as being Kerouac’s girlfriend first and a writer second (despite her three acclaimed novels, two memoirs and countless articles published in the New Yorker and Vanity Fair) said in a 2007 interview:

“It took me several years to finish [my] novel – much longer than anticipated because my life was chaotic, and interrupted by people like Jack.”

The wild culture of hard drinking, partying and casual sex might not seem to extreme to us now, but pre-Pill women had to balance their reckless, carefree lifestyles with the very real threat of being left high, dry and pregnant while their literary lover skipped town. More disturbing, though, was the willingness of families to institutionalise young women who broke with convention or stepped out of line.

“The 1940’s and 50’s saw women belonging to their parents first, and their husbands second, leaving their individuality limited, or non-existent,” says Katie Oates, writing for Beatdom journal.

Some were like Elise Cowen, the one-time girlfriend of Allen Ginsberg (when he was ‘experimenting’ with heterosexuality), whose lifelong struggle to fit into – and break free from – conventional society led to her hospitalisation, depression, and eventual suicide. Elise’s parents, disgusted and disgraced by her lifestyle, destroyed most of her work when she died. Others, regardless of their mental state, suffered a similar fate. At the Naropa Institute tribute to Ginsberg in 1994, Gregory Corso was fielding questions from the audience when a young woman asked him why there were so few female writers within the movement. Corso paused, then leant forward and said;

“There were women, they were there, I knew them, their families put them in institutions, they were given electric shocks. In the 50’s if you were male you could be a rebel, but if you were female your families had you locked up.”

However, in the 1950’s some women did manage to break through and make a name for themselves within the Beat circle and beyond. Diane Di Prima, Ruth Weiss and Joanne Kyger might not be household names in the same way that Kerouac and Ginsberg are, but their work is highly respected and, crucially, their success does not come with a “wife/girlfriend of THIS GREAT MAN” label attached. These Beat broads were a little younger than their male counterparts, and their careers weren’t defined by the chaos that often characterised the so-called Beat lifestyle. Switching between Manhattan and San Francisco, they immersed themselves into the brave new literary scene and wrote about their own experiences, rather than those of the men who surrounded them.

Kyger’s poetry and prose often focused on Zen Buddhist principles, Beat “philosophies” and observances of the minutiae of day to day life. Weiss was a jazz poetry innovator who kick-started creative gatherings for artists and poets in San Francisco, and whose work explores isolation, abstract thought, and female poets throughout history. Di Prima, perhaps the most prolific and well-known female Beat, was often slyly confrontational in her poems. Through her work, she pushed back at the societal expectations imposed upon women, poked fun at the rules and rituals her male counterparts espoused as essential disciplines for writing, and addressed head-on the marginalisation of women in the literary world. Throughout her lifetime she published forty one books and lectured at universities across the globe. She has outlived all of the key male Beats by at least 20 years, and wrote more books than Kerouac and Burroughs. Even Ginsberg, who was dismissive of most female poetic efforts, hailed her as a genius. Now 82, she doesn’t lecture often and has little time for interviews. However, as her husband Sheppard Powell tells me, “she still spends all of her time writing”.

Collectively, Kyger, Di Prima and Weiss published more works than the three ‘key’ Beats, yet analysis of their work has only recently broken out of the realm of feminist scholars and into the mainstream discourse about the movement. If we regard the Beat movement as a microcosm of the 20th century literary and publishing world, we can see that the persistent marginalisation of female writers is, to a large extent, something that is still a problem today. Female authors are still underrepresented on bookshelves and on publisher rosters. Books by women, about women still fail to make it onto global prize lists, and are often thrown under the patronising and dismissive ‘chick lit’ label. In 2011 the author VS Naipaul lambasted pretty much anything written by a woman as “feminine tosh” and stated “I think it is unequal to me.” Nice one, pal.

However, the tides are changing. Progress is slow, but constant. Editors, publishers and academics are paying more attention to the representation of women in literature, and respected publications are reviewing more female-authored work than ever before. The most interesting new authors and poets, though, are making their names outside of the mainstream publishing world. Poet and illustrator Rupi Kaur made waves through Tumblr and Instagram. Savannah Brown and Holly McNish perform slam poetry on Youtube, and it goes viral. Feminist DIY events, self-publishing, online subcultures and the resurgence of zines all provide valuable platforms for female voices. These days, millennial women are carving out literary counter-cultures of their own.

“Social media has massively changed the way in which we experience and interact with poetry,” says Jenn Hart, a 29 year old British poet who performs her work at DIY punk shows across the country. “I think with the rise of new wave feminism and identity politics in particular, instead of trying to integrate and break into male spaces, oppressed communities have taken and made their own space.”

If you can’t join ‘em, fuck ‘em. The Beat ladies would be proud.

–

Artwork by Kiki Saito for YEOJA Magazine. Check out #theWOCproject for more strong women.