Her photography has been shown in art shows all over the world, and she’s also…

Gretchen Andrew

Interview with the US based artist4 August 2020

Gretchen Andrew (@gretchenandrew) is known for her “search engine art”, where she uses SEO techniques to trick the internet into listing her images in top search engine results. These digital performances not only question the reality of what we see on the internet, but through the programming of feminine imagery within her search engine art, she also counteracts the male-dominated worlds of AI, programming, and the political control that they operate within.

Gretchen’s artist practice has included playful hacks on major art institutions such as Frieze, The Whitney Biennial, Artforum and the Turner Prize. We spoke with Gretchen to learn more about her search engine art, why she transitioned from working for Google to becoming an artist, and her reflections on the contemporary art world.

The internet turns out to have a huge flaw that you exploit in your art. Search engine algorithms can’t differentiate between something a user simulates and something that is actually happening. When you hacked yourself into the Frieze Art Fair you created a virtual gallery that looked just like Frieze’s venue and digitally placed your paintings there, and the search engine believed it. What did you do to make your digitally created images be one of the first search-results?

Gretchen: My process, what I call both “search engine art” and internet imperialism, involves exploiting the internet’s shortcomings in playful ways. Specifically, I focus on logical failings that make sense to humans but create chaos in the brains of computers and artificial intelligence.

There are differences between how humans and machines are able to understand context. Humans understand that eating a MacBook a day won’t keep the doctor away. The internet takes my images off my website that clearly states, “This site is in no way connected to the Frieze Los Angeles Art Fair,” and places them within search results for “Frieze Los Angeles.”

Growing up, when we studied the limitations and complexities of free speech, the teacher would use the example of not being able to yell “fire!” in a crowded building. Now we have Twitter and the internet and whatever you yell on Twitter you are yelling into an infinite amount of floating contexts. We can’t consider the context when evaluating free speech anymore because it’s constantly being renegotiated. That severing of context is one I exploit and explore in my work, and I welcome conversation about the implications.

Besides studying Information Systems at university, do you have any other skills or experiences that help you in your online artistic work?

Gretchen: Like many within my generation, I grew up on the internet. Until college, I lived in a small town in a small northern state that didn’t offer a wide world. My parents made a great effort to drive us hours to art museums in Boston or New York, and I think early on I found the internet to be a related, accessible form of travel and of escape which offered the opportunities of otherness.

You started as a tech-student at Boston College, then moved to the West Coast to pursue an artistic career as a painter. What revelations led to that shift in interest?

Gretchen: First I gave 18 months of working in Silicon Valley a try. I’ve also been reflecting on why I felt like I was more likely to succeed in art, something I knew literally nothing about, than in the tech world, for which I was formally prepared. There was a lot going on, but it wasn’t until I read Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley that I started to claim that part of the reason I left tech did relate to sexism.

When I started at Google, I decided every day I would eat breakfast at a different corporate cafeteria and randomly meet a new person. This networking was almost always interpreted as flirting, and after one really awkward guy tried to kiss me, I decided to stop. I also remember my boss telling me that my appearance mattered. Did it? I was working at Google; I thought that unwashed hair and zip ups were the default uniform. I’ve talked a lot about the other reasons why I left, but I knew I was thinking, where can I be myself? Ahhh, maybe art, I hear those people are free.

There’s another weakness that your art brings awareness to, which is that most internet-users tend to be pleased with the first results they see and they don’t verify information. Did you meet people actually referring to the “fake” results you’ve generated? Is there a lot of confusion on behalf of your persona?

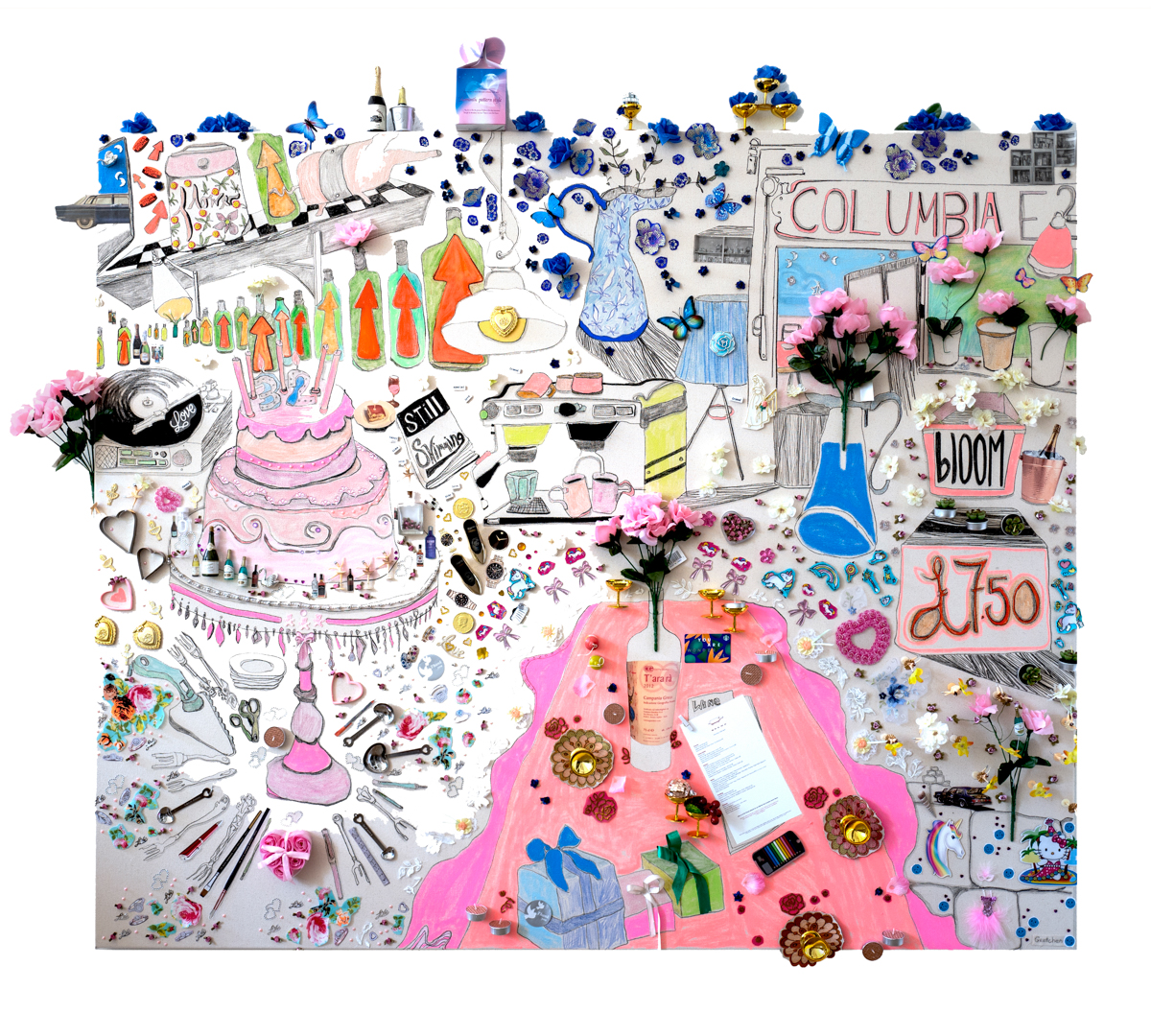

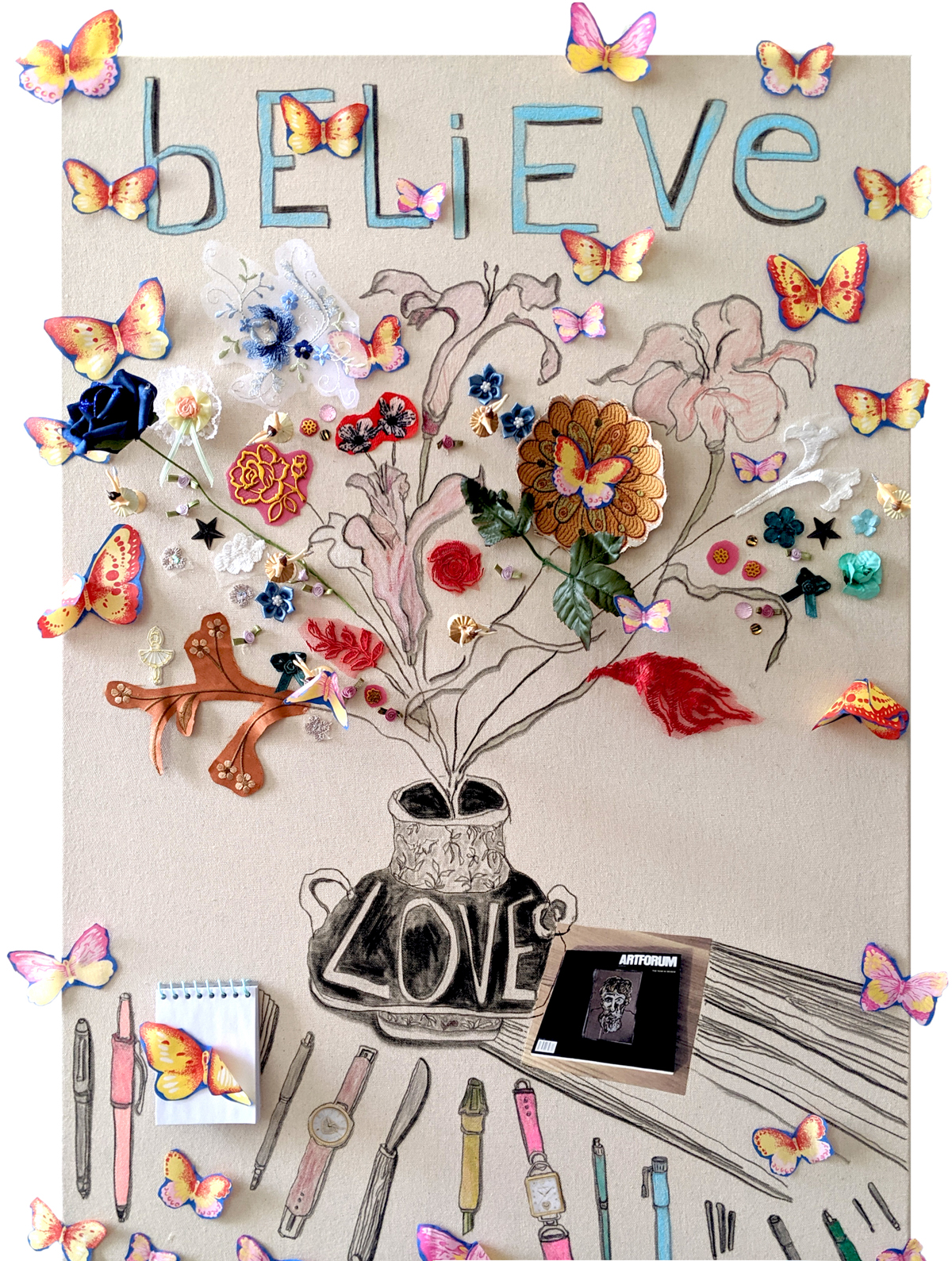

Gretchen: Since the Frieze Los Angeles project, I’ve turned my focus to making it obnoxiously clear that the images I create and program are not confused with “real” art world accomplishments. I do this by using vision boards that visually show the gap between my current life and my desired future.

When you started painting your mentor Billy Childish taught you from scratch. Back then you didn’t plan on giving your art that “search-engine-twist”. How was your approach different then from now? And why?

Gretchen: I was always gasping for ways to be integrated, who I was and also who I wanted to be. I knew I had something to offer outside of pure painting, so I was constantly experimenting with ways to connect my painting practice with technology, something I am unbelievably thankful to London’s Arebyte for supporting for so long.

Being a serious figurative oil painter, I ultimately was working towards an ideal and a form that wasn’t my own. By form, I mean all these unconscious beliefs about what an artist is, does, looks like, cares about. I’m obsessed with how Eileen Fischer and Sarah Blakey have built and run their companies, and being exposed to women like them, who recreate forms whether that is within art, business, fashion, film, or literature, this has given me a huge desire to do the same.

We would love to talk about your painting style. The thick lines and surreal color-choice remind us a bit of Maurice de Vlamnick’s fauvism phase. How would you describe your style and what inspires you?

Gretchen: I always felt like I made drawings that were closer reflections of myself, and then I almost, like, dulled myself down by covering them up with paint. I know this feeling is quite common among figurative painters, that to make a painting you must ruin a drawing, but I had been building this digital practice that I wanted to talk about, and I didn’t ever want to talk about the paintings. My paintings, learning to make them like I did, are how I chose my education and tradition. It’s where I built my confidence. They look like the paintings I love, though I have learned that loving something and wanting to become it are allowed to be different. The feeling of making my vision boards now, is that they incorporate drawing and some painting, but the feeling is all flow.

In an interview with Flaunt, you talk about at some point having grown tired of proving yourself, that you can paint and that you’re smart and a serious artist. Can you share your thoughts on the discrimination that goes on in the “elite art world”, and how you’ve experienced it?

Gretchen: I don’t want to blame the art world any more than wider cultural expectations of what “serious” looks like. I know I’m not what people think of when they think of a technology visionary either. My surname, Andrew, is a man’s first name and this has caused major confusion since my first exhibition six years ago, which was a combination of brooding oil paintings and virtual reality. I didn’t match the identity of a VR pioneer and all these people were showing up looking for a dude named Andrew. I thought, fuck, I can’t wear a dress to these things. I thought that I’d have to get old before I’d be taken seriously.

I’m over trying to navigate it. You can’t win. Bring on the dress and the heels! Embracing that is something I did in my Art Basel Miami Beach take over.

By the way, to cut confusion, I’ve been pushing for a first-name reference, Beyonce/Hilary style with journalists and such, so thank you for rocking with “Gretchen” instead of “Andrew” here!

In an Instagram post you talk about the Frieze-Fair “accidentally” approving your press pass. How did the traditional art world react to your recent subversive moves?

Gretchen: Institutional critique is a great tradition in the art world and I’ve found people enjoy the playful and aspirational nature of my work. I also don’t direct my work at people but at institutions, which are both symbols and conduits of power. But maybe people are a little afraid of me, too. I don’t believe in attacking or internet takedowns, but people must know I am more than capable of one.

In your recent work, you use flowers, glitter and cake topper ballerinas and apply them on your canvases that you call “vision boards”. By doing this, you play into a known cliché — the rookie female wannabe artist. By doing so you confront your viewers with their own expectations and preconceptions. Can you elaborate on that?

Gretchen: Right before I started making these vision boards public, I had a handful of men I love and respect unsolicitedly tell me they didn’t like them or didn’t get them. And it was the first time I really knew that my confidence was where it needed to be. I thought, if the only purpose of these are to prove to myself that I trust myself they will have been worthwhile.

It’s exciting to see so many different people embrace them. To get there I had great support identifying and working through imposter syndrome and importantly, spending a lot of time with my friends, a lot of whom are these badass high-powered banker women. Their power, independence, and material success are inspirational to me. They have become core to the content and feeling of my work, and spending time around them helps me tap into that.

When you manifest yourself virtually in these elite art venues you follow a sincere desire to “make it in the art world”. Desire, you mention in an interview, is a concept only known to the human mind. The machine does not know desire. It does not value the relation an individual has to an object, it just sees that there is one. Do you as an information scientist think that this will change one day? Can the algorithm be educated to have desire?

Gretchen: No, I don’t think so. I actually see AI getting dumber in a lot of ways. If our goal was only to make the most human-like AI then maybe. But instead most AI is being made with the motives of ease, efficiency, and profitability. Knowing and actually feeling also are different. An AI may be able to know of desire but ultimately I believe desire is something physically felt.

Your artistic message is a meta stance on the white female artist being goal-oriented and status driven. By manifesting the most exquisite artistic tributes (e.g. being on the cover of Artforum) you comment on what “making it in the art world” means to most people. We can imagine that a lot of viewers mistake your artistic position for actual naiveness. But if you could imagine art without the obligation of having connections and a status, what would it be like?

Gretchen: I know many great artists that don’t give a damn about art world success. But I think if you want to make a certain material living, be part of a history, a context, and a conversation, there is a system and a power structure to reckon with. I’m an artist that works with rules and systems and for me to personally thrive, I need a system to navigate.

And I am not hiding that. While I performatively work in this area, I am very goal-oriented and probably more than a little status driven. For me this probably comes from growing up without the feeling of economic security, of there not being a safety net that isn’t of my own invention. This occasionally threatens to make me scared and conservative, but instead I’m on a mission to get paid to be myself, something I think art gives me the best shot at. I think it’s possible to be performative, authentic, and sincere all at the same time, especially within femininity. But the major conceit of my vision boards is that what I desire way more than being on the cover of Artforum is time with friends and people I love. The Artforum magazine is a pretty small visual element in many of the works, while my sister and the Dorito bag on the beach are much larger.

And back to my female banker muse friends. I also find there is also something important and feminist about what they do, the status they claim. My work is so much about control and power, and money is deeply entwined with both. I don’t think it’s possible to separate my work from the simultaneous invention of its market.

What is currently on your vision boards? What will you manifest next?

Gretchen: Continuing my use of Sarah Thornton’s Seven Days in the Art World as my guide, I’m looking at a formal, “best MFA” arts education. The framework and content are around two years of money and life experience not spent on an MFA (Master of Fine Arts). Life, love, loss, friends, travel, Russian novels, political engagement, drugs, disappointment, and mentors being a great education. I’ll be sharing works from this series in my first show with Annka Kultys in Feb 2021.

_

Original artwork and photographs provided by Gretchen Andrew. Follow Gretchen on Instagram to keep up with her work. For more Art & Culture, click here.