Hi, DAMO. It’s great to sit down and chat with you. How would you introduce…

Apolonia Sokol

An interview with the French figurative painter17 August 2021

Apolonia Sokol (@apolonia_painter) is a French figurative painter of Danish and Polish origin. She grew up in the popular district of Château Rouge in the Parisian theatre Le Lavoir Moderne, where her parents took in a large number of intellectuals, writers, poets, and refugees.

She later welcomed various figures of feminism into her life with whom she formed lasting friendships, including Oksana Shachko, whose portrait she has painted several times. After graduating from the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris, Apolonia Sokol moved to the United States and settled in New York where she worked in the studios of painter Dan Colen and is Currently Sokol is on the Villa Medici residency program in Rome. YEOJA spoke to Apolonia about the meaning and inspiration behind some of her artwork, how she began painting, and why painting is still her medium of choice.

View this post on Instagram

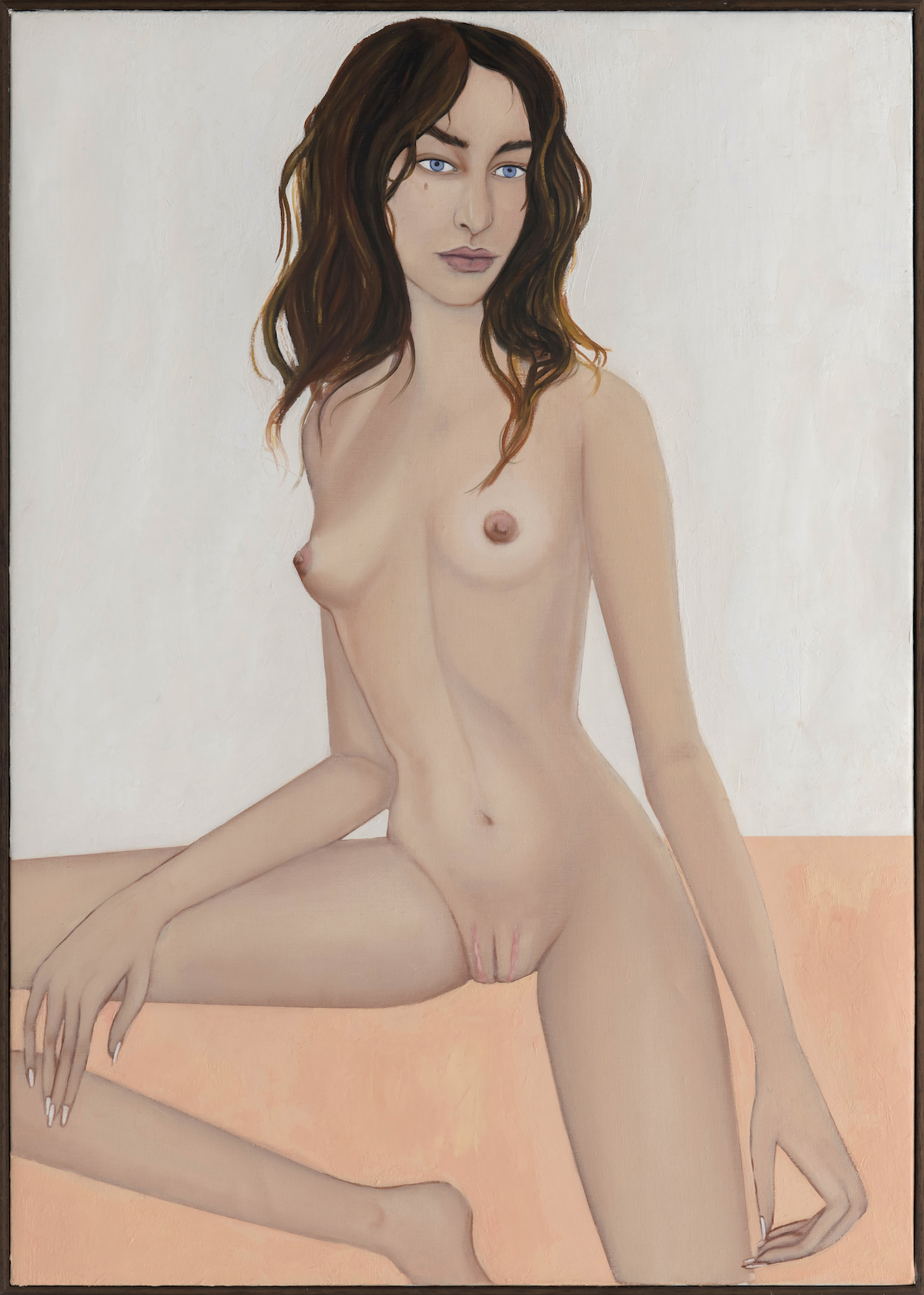

In this self-portrait, you depict yourself naked but your face is partially covered. You expose yourself but also manage to remain a mystery. Who is Apolonia Sokol beyond the canvas?

Apolonia: This painting is called Moi, which means “me” (in french). [I made it] at a vulnerable time. In 2016 I was quite desperate and disappointed after making naïve acquaintances with figures of power.

It refers to other pieces of art, made by men, [which is] probably due to my lack of self confidence. The anti-hero Edward Hopper was a minor artist during his time. He is now ironically appreciated for his lack of expression. His painting, Soir Bleu, 1914, was received unenthusiastically by critics and hidden in storage by the painter only to be rediscovered after his death. It’s a melancholic self portrait, with Hopper represented as a desperate sad clown, smoking a lonely cigarette while drowning himself in alcohol. Hopper was expressing his failure as an unsuccessful painter, who compromised himself with commercial advertising work. No doubt Soir Bleu was a cry for help and understanding.

I painted myself as a clown as well, with my face covered in white face cream. My piece is a commentary on the assigned role of the artist as a buffoon, used and abused by the upper class and more specifically the art market. In 2016, I was still very much a victim of sexual harassment and mistreated by speculators in the art world. It comes as no surprise that this particular environment can be a niche for malicious people. Being a young female painter, I was often discouraged; but I never lost hope. Hopper could hide behind his questionable compromises in a Pierrot outfit. I, as a woman, have to wear my skin and my body, which has been compromised in its own way.

My naked self is also referring to a magnificent and extremely disturbing piece by Munch, called Puberty, 1894–95. A young girl, not yet a woman; is sitting on a bed naked in discomfort. Her arms are crossed as she tries to hide her nudity. She is oppressed by her own shadow, which has an unclear shape. Perhaps it’s her soul leaving her body. The shadow might also represent the painter himself a threat to the teenager, with rape culture being a major part of western civilisation and its art history.

Photography: Daniele Molajoli

Your self-portraits are unique. What does the process of depicting yourself trigger in you? Have your self-portraits changed over time?

Apolonia: My self-portraits have changed, as over the years I have grown into an unbreakable being. At least, I hope I have. I include myself in some of my pieces, as they are life stories of people I know, admire, cherish or miss, but my work is not based on self-portraits.

You have a very distinct style that makes your paintings recognisable at the first glance. How did you begin as an artist?

Apolonia: I have always painted. I grew up in a small underground theatre in the Parisian African neighbourhood, among Senegalese, Malian, Algerian, and Ghanan communities. It was a true crossroad of diversity and a cultural melting pot. Artists, musicians, writers, poets, all personalities from the underground, LGBTQIA+ communities, and people from different faiths would meet in this house, or on my street. I must say it was very prolific even though we had no money – nobody did. I learned to paint with my mother’s best friends. They were street portraitists of Polish immigration. One could think it was sometimes a violent ambiance, with various political discourse and intrigues, drugs, sex work, and alcoholism, but I think it was the best place to flourish in. Criminality in this area was and still comes down to gentrification, bad politics, and police violence.

There are a lot of multidisciplinary artists out there making prints, coding, and painting at the same time. You on the other hand focus solely on painting on canvas. What is it about painting that makes it your medium of choice?

Apolonia: Painting is a physical matter, oil paint is made of natural elements. Pigments are sourced from the earth. Plants and stones are incorporated into arabic gum and oil. Turpentine is the essence of pine trees. Canvas made of pure linen. I think we are in osmosis with these elements and there is a physical attraction to them, just like the attraction we have to the ocean or other gifts of nature.

Humans have always been attracted to pigments. In order to paint prehistoric murals, our ancestors had to walk sometimes more than 100 kilometers to find pigments, even with the risk of bad weather or being attacked by animals, with many dying on these missions. For instance in October 2020 in Fontainebleau, south-east of Paris, a marvellous installation was discovered deep down in a cave. It’s a hydraulic system, in the shape of a vulva, activated only by rain. It’s a 90.000 year old piece of hydro and ecofeminist art, made of the beautiful natural materials of stone and water.

In 2019, another striking discovery occurred with the discovery of a German Nun buried in the year 1000. Her teeth were encrusted with Lapis Lazuli, an extremely rare pigment. This pointed to the Nun’s work as a painter or scribe (or both) who illuminated manuscripts

This discovery raises the topic of gender and the status of women in western society. Not only was the nun extremely powerful since she was a scribe, in possession of knowledge, one of the very few to write in these times; she was also connected to a largely developed network, as Lapis Lazuli is only to be found in Afghanistan.

I’m a painter because of all these reasons and many more, but especially because I love doing it.

View this post on Instagram

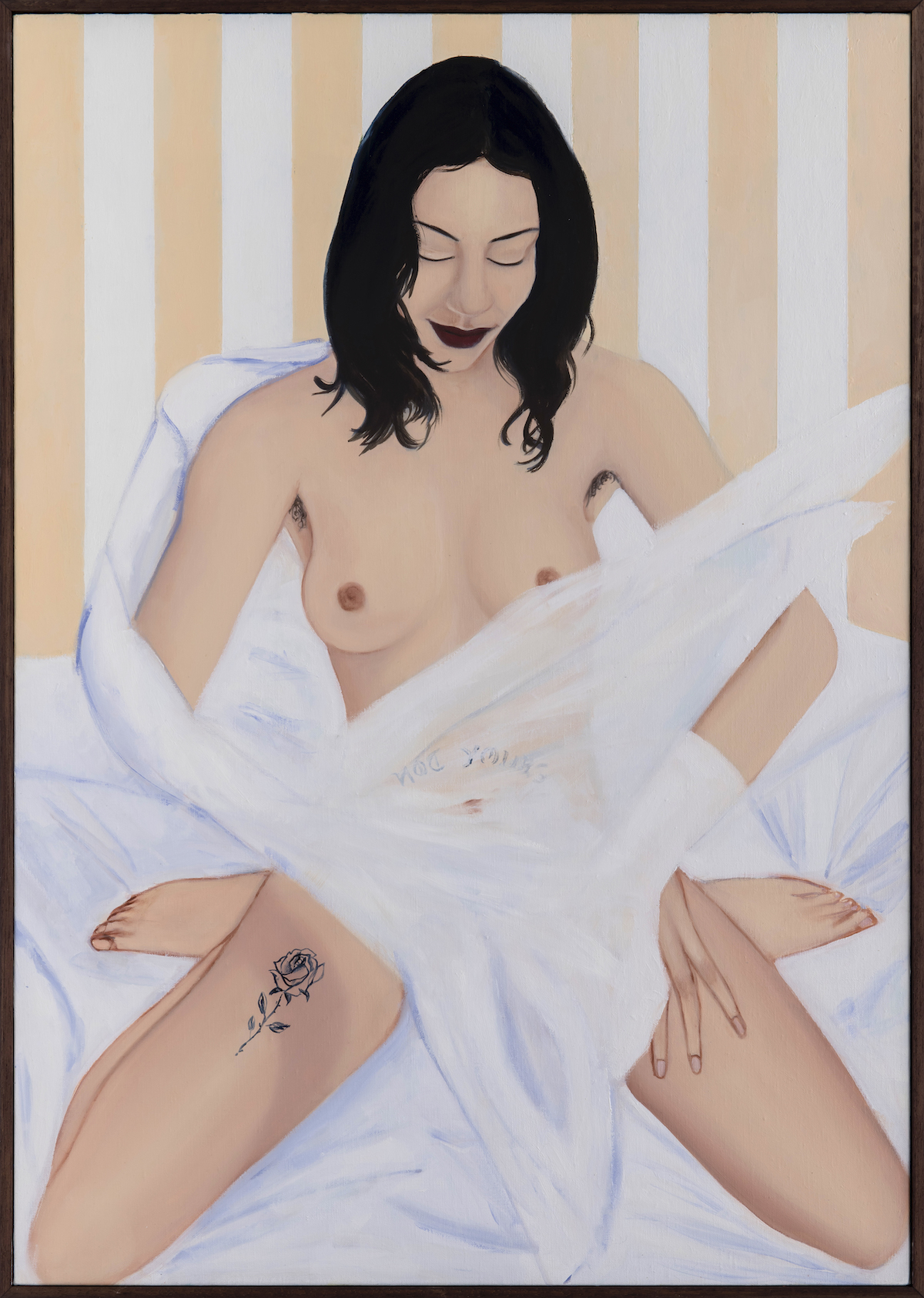

This painting of yours is reminiscent of Chagall’s “Flying Lovers” painting. How do you feel about this comparison? Which personalities, if any, would you mention as defining your aesthetic and message?

Apolonia: Thank you for your observation. I believe art is a language and one can practice its vocabulary by referring to other pieces. It is a free language with many dialects, both universal and personal. Interpretations are endless just the way culture is. This painting refers to The Sleepers by Gustave Courbet. Courbet was one of the very few painters engaged In political activism, and was very much ahead of his time. He tried to evoke queer identity as much as he could, yet his painting of The Sleepers is represented by the male gaze. A voyeur admires two lovers sleeping deeply after a passionate night. I wanted to reclaim this scenery. Anouk [the person in the painting and the name of the piece] and myself are looking the viewer straight in the eye, fully dressed; our intimacy is our own.

We noticed that one of your Instagram posts is titled the ‘Polish matriarchy’. Can you tell us more about it?

Apolonia: This picture was taken at the hospital in Poland a few months before my grandmother passed away. We managed to gather one last time. My aunts had been travelling for days by bus all the way from Minsk, Belarus. Aunt Ada came from California, my mother and I from Paris. We love each other very deeply although the diaspora has separated us physically. We are very lucky to know each other. My grandmother was deported to the Stalinian gulags in Siberia during the war and separated from her family. May she rest in peace now.

In a post that includes Femen co-founder Oksana Shachko, you share information about the ongoing police brutality in Belarus. Why do you think art and activism form such a prolific bond?

Apolonia: Oksana was my best friend, and also a painter, so we connected deeply on the artistic level. I don’t believe in a formula such as art and activism, although I think art has to be sincere and sometimes art and activism combine into one being like Oksana Shachko. That is a gift to humanity.

I was never an activist or a [member of] Femen, although I brought the movement to Paris and was hosting [members of Femen] in my house. Oksana*, along with Sasha (two co-founders of Femen) became estranged from Femen, due to internal conflict with Inna Shevchenkho and the remaining members of the group. The original intention of the group had also shifted away from what Oksana believed in. Oksana was left without housing, recognition, or support. Oksana found herself in a deplorable situation, robbed of her ideas and art, and lived in extreme poverty. Tragically in 2018, she died by suicide in fatal desperation.

I’m extremely concerned by the extreme police violence in the dictatorship of Belarus, my Belarussian cousins are fighting for their rights.

Art has always been a dialogue. Different movements and aesthetics have evolved by artists quoting and appropriating each other’s work. What are your thoughts on cultural appropriation, specifically in the art space?

Apolonia: As I was writing before, in my opinion art is a language so it does re-use elements of others, in the form of hommages or references. Now cultural appropriation is another topic, a very important one in the context of western attitudes in relation to colonial and post-colonial situations.

Culture is a legacy, it goes hand and hand with power. And it can be an instrument of domination. Unfortunately art is often used as a medium for propaganda in the service of power. Art is putting ideas in form and shaping philosophies. Because art is so open to interpretation, there are multiple possibilities of understanding a piece. The message can be vague, or subconscious. Pieces of art are also anachronistically reinterpreted according to present philosophies.

Art can also be wrongly interpreted or have problematic origins. For Example, Gauguin’s beautiful paintings representing the Tahitian community, were and still are very much appreciated for their vivid palettes, calm ambiance, unique style, and romantic depictions of French Polynesia. In actuality, Gauguin arrived in Tahiti as a white man, married several 13-14 year old girls, and spread syphilis on the island which led to a form of genocide.

As long as we haven’t demolished our icons, we cannot move forward. But it is a vicious circle. If art is a legacy, people in the art world are not allowing their knowledge and financial investments within them to be dismantled. This is probably why the art world is having such a hard time with decolonizing the arts or the #metoo movement – especially within Europe.

Are we ready to change our iconography? Personally, I think I am. I visualise art history and it’s biodiversity as an iceberg. Above sea-level is the tip of the iceberg made of up visible “official” icons, like Picasso. Below sea-level are all the unknown artists and artefacts that have yet to come to light. I believe there is absolutely no harm in discovering them. Among them are undoubtedly the African pieces stolen by Europeans, rotting in French and Belgian museum basements – pieces that Picasso himself copied.

My partner Azzedine Saleck is a bedouin poet and sculptor, his views on materiality are quite fascinating. Actually the legacy of the Saharian desert is mainly poetry. Bedouins from all over the globe gather in Abu Dhabi for a poetry contest each year. When visiting Mauritania, I naively asked his father where I could read the poems, the treasures of the desert. To my big surprise there are no writings, or traces of these magnificent pieces of art. If written versions are to be found they are never to be translated in a language [of a colonising power] I could read. Oral transmission is a method of preserving the arts from cultural appropriation and colonisers. I say, Bravo to that.

You are a recent resident of the famous “Villa Medici,” a renowned art institution. Congratulations! Did receiving public acclaim change your approach in any way?

Apolonia: Yes I am on a one year residency in Villa Medicis in Rome. It’s a magnificent palace on the city’s highest peak. It has several hectares of French and Italian gardens, peacocks, and a rare collection of orange species. It’s a government program and we have quite a significant stipend. The interiors of the castel are also decorated with colonial tapestries representing a display of French wealth, such as Congolese slaves on a convoy to Brazil, and indigenous people among fauna and flora. All the plants and animals imaginable are represented, symbolising the endless resources to be exploited by the white man, the French king.

In the garden there is the statue of Colbert. Colbert was a famous French administrator who co-created the art residency at its original location of Palazzo Capranica in 1666. Its imperialist tradition is for renowned artists to be sent to copy the old masters, as well as to represent France abroad with the “The Colbert Mission.”

A few years after co-creating the residency which was founded by Louis XIV, Colbert would write the Code Noir (Black Code) ruling which punishments would be inflicted on the slaves, the “furniture” of the empire. In my opinion his philosophy continues to have an impact and is simply known by more insidious and indirect names: Industrialisation. Capitalism. And here I am in the heart of this legacy. I’m receiving public acclaim because of my work, of course. Nevertheless, I’m trying to help this institution to look at itself and come to terms with [its direct ties to colonialism and imperialism]. I’m exhausted. I can’t fathom the struggles of BIPoC communities.

_

*If you are interested in reading more about Oksana Shachko, Nicholas Mir Chaikin wrote a piece about Shachko for Vulture, which you can read here. To follow Apolonia on Instagram, click here. For more interviews, click here.