Xinan Pandan lead a hands-on creative screen printing workshop where participants were able to screen…

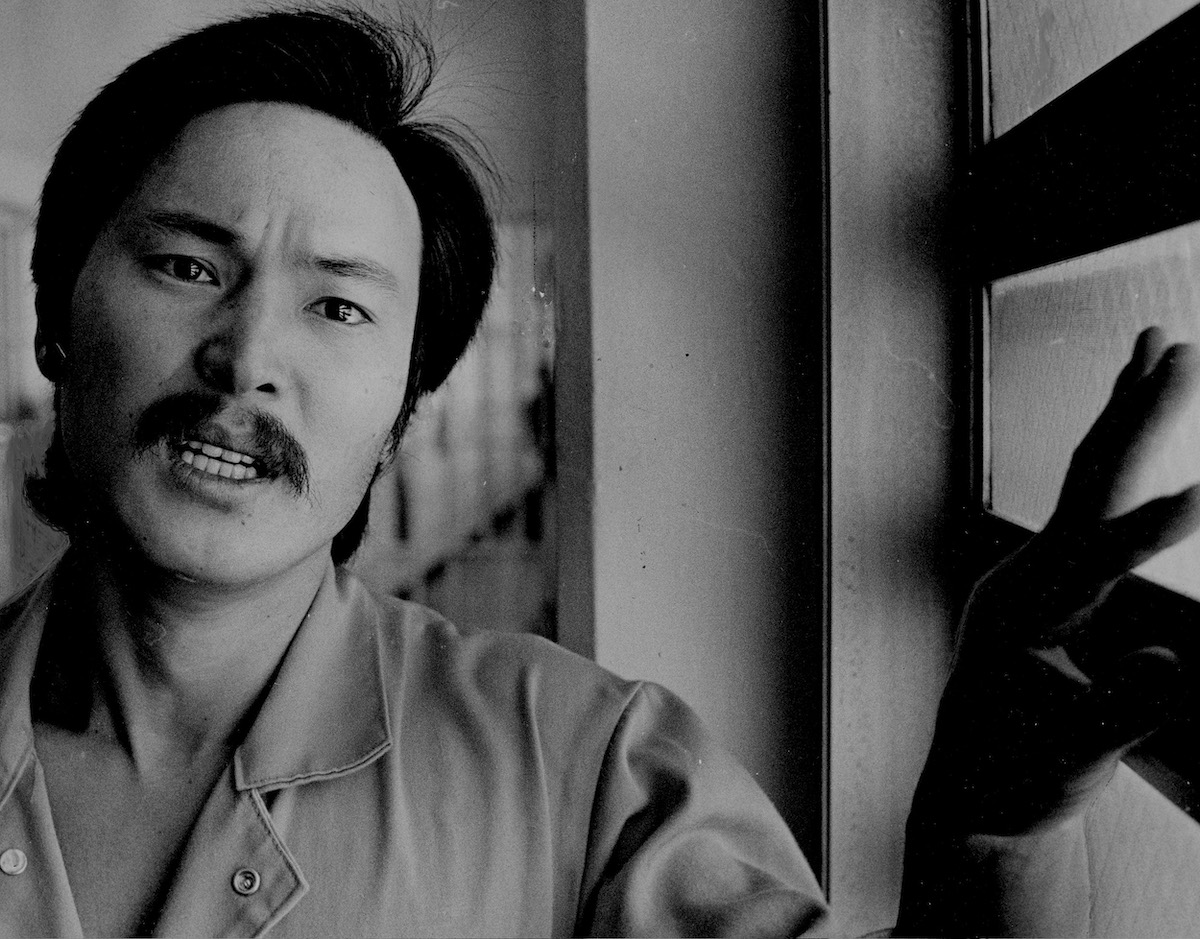

Chol Soo Lee – The Asian Diaspora and the American Prison Industrial Complex

An interview with the directors of documentary "Free Chol Soo Lee"26 January 2023

One of the specific ways in which racism impacts members of the Asian Diasporic community in the global North, especially in the United States, is an astounding lack of knowledge about the ways in which systemic and systematic racism has directly impacted the Asian Diasporic community.

This discourse is only slowly making its way into conversations. At this point, most know about Vincent Chin, Chinese Exclusion act and the Japanese internment camps. And yet, I was unaware of San Francisco’s war on Filipino elders in Manila Town in 1968, which was recently covered by VOX as part of their series Missing Chapter, which focuses on underreported and ignored pieces of history. I also only just learnt of one of the United States’ largest mass lynchings where 19 Chinese Americans were murdered in 1971, or the KKK’s targeting of Chinese immigrants. “Free Chol Soo Lee” explores another area wildly under-reported: the ways in which Asian Americans are impacted by the prison industrial complex. I sat down to chat with directors of the film, Julie Ha and Eugine Yi to talk about the importance of narrating our own stories, highlighting Asian American stories in the aftermath of the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, and more:

Despite the 1983 documentary, ”Perceptions: A Question of Justice” and the 1989 film, “True Believer” showcasing Chol Soo Lee’s story, Lee’s case remained a largely unknown piece of American history. This is unsurprising considering the fact that in “True Believer”, Chol Soo Lee’s story was little more than a plot device to prop up two white protagonists as a dynamic attorney and legal clerk. (This is further evidenced by both the trailer for “True Believer” referring to the character based off of Chol Soo Lee as simply “someone” and “Eddie Dodd”, the spin-off created, which focuses on a [white] lawyer.) Julie, in an interview with The Atlantic, you stress the importance of Asian Americans telling their own stories. In what ways has telling this story been significant to you both as Asian Americans?

Julie: I think we’ve long known that this story would be one of the most important we’d ever tell. It’s such a singular story and one that’s hugely consequential, especially given the times we are living through. In our film, Asian Americans are allowed to be seen in roles we’re not used to seeing them in: the victim of racial profiling and railroading in or criminal justice system, the heroic journalist who exposes the truth, the activists who lead a movement of resistance. When you read these descriptions or hear about them, there’s almost a mythical quality to them because we’re typically erased from the narrative – even when it’s the truth and it really happened. So, it’s been very heartening and meaningful to tell this story, where Asian Americans get to take their rightful roles in history and folks who look like us are allowed to be fleshed-out human beings.

We’ve said that we believe this film has the power to change how the public at large sees Asian Americans, but also how we Asian Americans see ourselves – and perhaps, even our roles in creating a more just society for all.

What has it been like to work on a project where the majority of folx involved (both in front and behind the camera) are Asian Americans?

Julie: Eugene and I, who previously worked together as journalists for a Korean American magazine, have long shared a passion for telling complex Asian American stories with nuance and depth. And we’re very proud that, for FREE CHOL SOO LEE, we had an incredible team of Asian/Asian Americans – including producers Su Kim, Jean Tsien and Sona Jo, and our narrator Sebastian Yoon – who brought their lenses, considerable talents and dedication to making this film. We also feel honored to have had the trust and support of the Asian Americans who lived this story and shared it with us with such openness and generosity.

It often takes contemporary injustices to spur exploration and interest in the lives and stories of non-white folx in the mainstream consciousness. Do you feel that the increase in racism Asian folx have faced worldwide in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent dialogue generated around it impacted how “Free Chol Soo Lee” has been received by audiences and media outlets? Additionally, you have spoken about how the pandemic logistically impacted the process of making this film, but how did the increase in anti-Asian sentiment impact your process?

Julie: Of course, we were well aware of the anti-Asian atmosphere during our final years of working on this film, but I don’t think it changed the story we wanted to tell and how to tell it. Ultimately, we had to stay true to our north star – which was centering the story of this complicated man, Chol Soo Lee, and trying to cover the full arc of his life through a humanizing and compassionate lens.

As for the film’s release in this same atmosphere, that has definitely contributed to how audiences have received it. Overwhelmingly, people – especially Asian Americans – come up to us after our screenings and say, “Thank you for making this film.” Many say they had never before heard the story, but after learning of this history, you can tell that they are profoundly moved – perhaps even transformed in some way. They are connecting the dots between what’s happening now to Asian Americans and the racism we experienced throughout our long history in this country – an often unknown history. One person who saw the film in Chicago said afterwards that, after watching our film, he now considers Chol Soo Lee one of his ancestors. Another person, a Korean American woman who shared that her late brother was formerly incarcerated, said that the film gave a voice and face to families like hers who often feel stigmatized and unseen within our own community. Young activists and journalists are also feeling inspired after watching the film and bearing witness to the righteous work of these people in the Free Chol Soo Lee crusade. In other words, the legacy of Chol Soo Lee lives on through people who are watching the film today and personalizing its message.

View this post on Instagram

Is this first and foremost a film for Asian Americans, or is it equally intended to be a film for non-Asian POC Americans, Black and Indegenious Americans, and white Americans? Are the take-aways universal or are there different messages you wish to communicate to different communities watching?

Eugene: We always hoped that our film could reach any audience member, regardless of race. There is so much in Chol Soo Lee’s story that is universal. But there is special resonance for Asian Americans, of course. As Julie has referenced, there aren’t many places where we can literally see ourselves in a story like this. So we always hoped that our film could help spur Asian Americans to be involved in conversations surrounding the topics and themes that emerge from our film: criminal justice reform, re-entry, addiction, to name a few. But more broadly, we hope that all audiences can see that when it comes to the forces that shaped Chol Soo Lee’s life, there is more that binds us together than keeps us apart. These are issues that affect us all. And it’s been gratifying to see that audiences—Asian American and not—have been receptive to this type of message.

What are the critical questions you want viewers to leave the film asking?

Julie: We try not to be too prescriptive and instead like to encourage individuals to personalize the message for themselves because this film, this story has so much to impart. Some see it as an indictment of the American criminal justice system and a wake-up call to the human damage of mass incarceration. For others, it’s arming them with this sense of history and they are able to connect the dots between what’s happening now in the United States – this horrible spike in anti-Asian violence – and the racism our community has experienced ever since first arriving on these shores. This is often a history that is not known or acknowledged. But part of this history, too, is this remarkable movement of resistance led by Asian Americans who stood up to one of the most powerful institutions in this country – the criminal justice system – and boldly asserted, “You did wrong, and we’re going to right this wrong.”

Not only that, but they also asserted that this poor Korean immigrant man – who was no model minority, actually, but did have a criminal record even before this injustice occurred – was worthy of their time, attention, love and care. And this courageous and compassionate act connects to one question we’d like audiences to consider – it’s one that Chol Soo Lee himself expressed before he passed: “Who are the other Chol Soo Lee’s in our society – the unseen, unheard, the voiceless, or forgotten?” In this way, we’d like the film to help extend a lasting legacy for Chol Soo Lee and the movement he inspired.

View this post on Instagram

This documentary also made viewers aware of other Asian Americans like Korean-American journalist K.W. Lee, who wrote an investigative series on Chol Soo Lee’s wrongful conviction and imprisonment, and third generation Japanese-American college student Ranko Yamada, who was part of the first Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee. That is to say, this documentary is not just a story about Chol Soo Lee, but a story about countless other Asian Americans who mainstream media may have ignored but were nonetheless not only instrumental in the fight against racism towards Asian Americans but are individuals with their own stories. Have either of you thought about future documentaries on K.W. Lee or Ranko Yamada? Or are there other unknown stories from the Asian American community that you would like to center in a future documentary?

Julie: K.W. Lee, Ranko Yamada and many, many others involved in the Free Chol Soo Lee crusade deserve their own documentaries, definitely. And there are indeed a wealth of unknown Asian American stories that can make compelling documentaries. As I worked on this film, so many ideas started percolating! But, personally, I do miss my first love – writing – and have some projects that I’d like to dive into. Whatever the form, I’ll definitely continue to tell stories, and many of them, Asian American-centered ones.

Eugene: There are so many stories that need to be told! And the communities that make up Asian America are so varied and vast. But I think I’ll always be interested in stories that have to do with meaning and memory, from an Asian American perspective.

View this post on Instagram

Julie, K.W. Lee is also your mentor. You also explained that K.W. Lee’s indignation towards the lack of public knowledge surrounding Chol Soo Lee’s wrongful incarceration after his [Chol Soo Lee’s] passing in 2014 was also a catalyst for the creation of this documentary. How has K.W. Lee felt about not only the film itself, but the amount of coverage the film and thus Chol Soo Lee’s life has received?

Julie: You know, I was just talking with K.W. about this, and he was so wowed by how the Chol Soo Lee story, told cinematically as a documentary, has reached and moved so many people – and in a very deep way. He feels like the film has allowed for a conversation between Chol Soo Lee and people today, especially Asian Americans or diasporic Asians in general – that there’s almost a kind of telepathy at work. Chol Soo Lee is “feeding” their sense of history about themselves, as well as their empathy, K.W. said. I thought this was such a beautiful reflection on the impact the film is having. As for the film itself, K.W. said after watching it for the first time: “At last, Chol Soo Lee is free.”

View this post on Instagram

You both have been making the rounds and being interviewed by many media outlets in relation to this film. Are there any questions you are tired of answering and are there any questions you wish people would ask?

Julie: Haha. Speaking for myself, it’s not so much that I get tired of answering the same questions, but it’s hard to get used to hearing and reading one’s same answers aired or published over and over again! I want to make sure that I speak with conviction and genuineness each time, even if I’ve answered the question 30 times in the past. In terms of questions we wish people would ask, we always like an excuse to talk about our remarkable narrator, Sebastian Yoon, who voiced Chol Soo Lee with such genuineness, care, depth and heart. In collaborating with us on the script for what Chol Soo says in our film, he also helped us better understand Chol Soo’s internal journey while he was incarcerated – the depression, the loneliness, the dehumanization – and how hard it must have been for him to battle those demons once out. Sebastian said that, because Chol Soo is no longer with us, he felt an obligation to speak up for him. He wanted audiences not to judge Chol Soo for his failures after his release, but to see him, listen to him with understanding and empathy. I think you can feel this intention in Sebastian’s narration. Our film team feels so fortunate to have worked with Sebastian and to know him.

Eugene: For me personally, I’m still in awe of the fact that there is so much interest in the film! So I’m happy to talk about any of it. I will just add that it’s always a thrill when the activists themselves are interviewed in a story, or take part in a Q&A. They are just so inspiring. I find myself wanting to just listen in! And their presence at a panel discussion turns that space into a forum for intergenerational connection. It’s just been wonderful to see the ways they’ve been able to interact with audiences in that way.

A running theme in the Asian American story is that it is a history whose past and present is not forgotten but ignored – for in order to be forgotten something has to have once been known about in the first place. This erasure of Asian American history is, in my opinion, a lesser talked about component of the model minority myth. By denying the impact the carceral state and racist policies have had/have on us and failing to make historical events like the Rock Springs massacre a part of American education, we are not only being told we are not part of American history, we are also denied the recognition of the systemic, institutional, and systematic injustices imposed upon us.

Additionally the (racist) notion that Asian Americans are better behaved, smarter, and harder workers, compared to other BIPoCs, not only further pits Asian Americans against other BIPoC Americans but weaponises us against other BIPoC folx. The telling of Chol Soo Lee’s story brings Asian Americans one step closer to being part of conversations about criminal justice reform and the prison industrial complex. In what ways do you feel “Free Chol Soo Lee” helps fight against our erasure and the model minority myth? And were you both consciously looking to open up this dialogue with this film?

Eugene: The erasure you mention fuels another stereotype: that of the perpetual foreigner. This stereotype questions our American-ness, our very right to be in this country, our very right to exist. A lack of awareness of our history allows this stereotype to continue to fester. So to know our history is to fight this stereotype as well. It roots us here.

It bears pointing out again the unlikeliness of the solidarity that fueled the Chol Soo Lee movement. It wasn’t expected that immigrant Koreans and American-born Asians—many of them of Japanese descent—could come together like this. One must remember that the Japanese occupation was still in the living memory of many of the older Korean immigrants who worked on Chol Soo Lee’s case. But in the case of the Chol Soo Lee movement, people with disparate histories and backgrounds were able to come together and find common cause in Chol Soo Lee’s plight.

So restoring this history to our communities teaches us about historical injustice and oppression, yes. But it also teaches us about our history of resistance. As Jeff Adachi, the former public defender of San Francisco said to us in his interview, it wasn’t considered an “Asian American thing to do, to say to the system, ‘You’re wrong.’” Or, to put it another way, that’s not a very “model minority” thing to do. But that’s just what they did. We’ve long hoped that these types of conversations could be fostered by our film, and we’ve been gratified to see that that has been the case.

Eugene, in an interview with Asian Movie Pulse you touch upon “the power of the archive itself”. You also mention that the archival material shown in this film wasn’t found in an official archive house but was acquired by reaching out personally to those involved with the movement at the time and digging through their personal material. For marginalised folx whose histories are not told and/or suppressed by mainstream media, our personal archival process is very much a defiant and political act in and of itself. It allows folx like yourself and Julie to call upon these tangible memories as evidence to create a public archive and show society that our stories were and are real and they/we will not be erased. What are your thoughts on this?

Eugene: You hit the nail on the head. For there to be an archive, there must be an archivist. And Asian Americans connected to the movement decided to archive what they had, carting and storing boxes for decades, creating what we’ve come to call an underground archive of material related to Chol Soo Lee. They recognized the seminal nature of this history. And they created the community archive that made our film possible. A special shout has to go to Sandra Gin, a television reporter who created a news program in 1983 exploring the Chol Soo Lee case. It ended with his release, but she interviewed Chol Soo Lee later in his life as well. She shared her footage with us, an act of generosity by which we remain humbled and grateful. It’s really been a privilege to connect with this generation of activists and journalists in this way. In addition, we were able to buttress this community archive through the work of our talented archival producer Brian Becker, who is a director in his own right. He unearthed much rich material, including the radio commercial for K.W. Lee. Here was a commercial for a mainstream newspaper in the 1970s using K.W. Lee as their star reporter, to try and sell papers. It’s almost impossible to imagine, but that’s the power of archival. You don’t have to imagine it because the archive is there.

View this post on Instagram

Lastly, in what ways has this process brought you both, as well as activist and film narrator Sebstian Yoon, closer together and what does 2023 have in store for you both?

Julie: There’s actually quite a neat story about Sebastian that we love to share.

When our producer Su Kim first reached out to Sebastian in 2021 to ask him to work with us, to our surprise, he revealed that he knew of me from a magazine I used to work for. I was formerly the editor-in-chief of a Korean American magazine called KoreAm Journal. That’s actually how Eugene and I first met — he was a contributing writer/editor. Sebastian told Su he had once written a letter to the editor from prison and I published it — and it was the highlight of his year. When I learned this, I searched for the letter and found it — it was the most amazing letter from a decade earlier. He wrote that he was nearly five years into a 15-year sentence, having first gone to prison at age 16. A fellow incarcerated Korean American had shared a copy of our magazine with him and so he started to subscribe. Reading the stories every month, he said, gave him some joy and a sense of community, especially in an environment that could be stoic and depressing — where he did not see many other Korean faces. He also said that he hoped our magazine could help shed light on the problems of Korean American youth, who, lacking direction and support, get caught up in a self-destructive lifestyle, doing drugs and joining gangs, as he had. We are all not model minorities, he said. He lamented how, behind bars, he could not do this himself, but maybe our magazine could.

I still get pretty choked up just thinking about how the person who wrote that letter would turn out to be the same person whom Su almost instinctively felt could be the voice of Chol Soo Lee. And now we are all connected by this film. We get to fulfill the wish that he wrote about 10 years earlier. As we’ve had a chance to share the film over the past 11 months, we see how it’s making people think about the unseen and unheard in our society, the other Chol Soo Lee’s — including at-risk youth or those members of our community who are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated.

When Sebastian has participated in our post-screening Q and As, he speaks so honestly and movingly about his own incarceration, about the issues of reentry and recidivism, and connects with audiences in a very deep way. Many are often left in tears. He has said that he himself connected quite profoundly to Chol Soo and felt the need to speak up for him, since he is no longer with us. He wanted to help people understand all Chol Soo had to overcome — including the demons of incarceration — long after he was released from prison. He wanted to “remind society that we could be kinder and more empathetic if we truly took the time to learn about and listen to one another.”

We often say that, when Sebastian joined our team, everything fell into place. It has been an incredible gift to work with him, and get to know him on a personal level. He’s such a kind soul and courageous young man. And there’s something almost magical about how all of this happened. The stars truly aligned. We think Chol Soo himself would have been happy to know Sebastian voiced him and helped tell his story.

View this post on Instagram

Eugene: For the coming year, we’re continuing to get the film out there! Our American broadcast premiere will be in April, on public television. That will be accompanied by conversations with community partner organizations across the U.S., and we’re working with our wonderful team at public television to create discussion guidelines to make those conversations as fruitful as possible. Being on public television is important for us, because it’s one of the few networks that are broadcast in American prisons. So it’s a way to reach the incarcerated population here.

Our film will also be released theatrically in South Korea next year, and we are just over the moon about it. We had our Asian premiere at the Busan International Film Festival, and we got a sense of the South Korean audience’s reaction to the film. So we’re excited to continue those conversations. And there’s also educational outreach, which we’ve always felt was supremely important. We feel strongly that this film and this story should be taught as part of any Asian American history curriculum. To that end, we have screenings planned at some universities next spring, and look forward to continuing that work.

So we have a lot of work related to “Free Chol Soo Lee” coming up! But it’s a gift, really. The reaction from audiences has just been extraordinary, and the potential for further reach is great. So it feels only right that we work to ensure that the film can be as impactful as it can be.

_

Paid partnership with Mubi Deutschland. Images provided by Mubi Detuschland. To learn more about Free Chol Soo Lee, visit the official website here. To read more stories about the Asian Diasaporia, click here.