Kikelomo Kikelomo is a London-born, Berlin-based radio presenter and DJ. She hosts the radio show…

Ari – The Peace Statue for Korea’s Comfort Women

and a growing symbol of global resistance and solidarity8 July 2025

Korea Verband e.V. is a Berlin-based nonprofit organization dedicated to fostering understanding, dialogue, and cooperation between Germany, Korea, and the global community.

Since its founding in 1990, it has worked tirelessly to promote social justice, cultural exchange, and human rights, particularly in relation to Korean history, politics, and diaspora issues. One of its most well-known initiatives is the installation and defense of the Peace Statue, known as Ari, which stands as a powerful symbol of justice for the victims of wartime sexual violence.

The Peace Statue Ari is located at Bremer Str. 41, 10551 Berlin.

In a conversation with four activists from Korea Verband, Youngsook, Nataly, Ngân and Jana, they shared their insights on the significance of the Peace Statue, the ongoing struggle for its recognition, and the broader implications of their activism:

Nataly: The History of Ari and the Struggle for Recognition

Nataly traced the origins of the Peace Statue back to December 14, 2011, when the first statue was erected in Seoul to mark the 1000th Wednesday demonstration demanding justice for the so-called “comfort women”. The movement quickly spread, with statues appearing in other countries, including the United States in 2016 and later in Berlin.

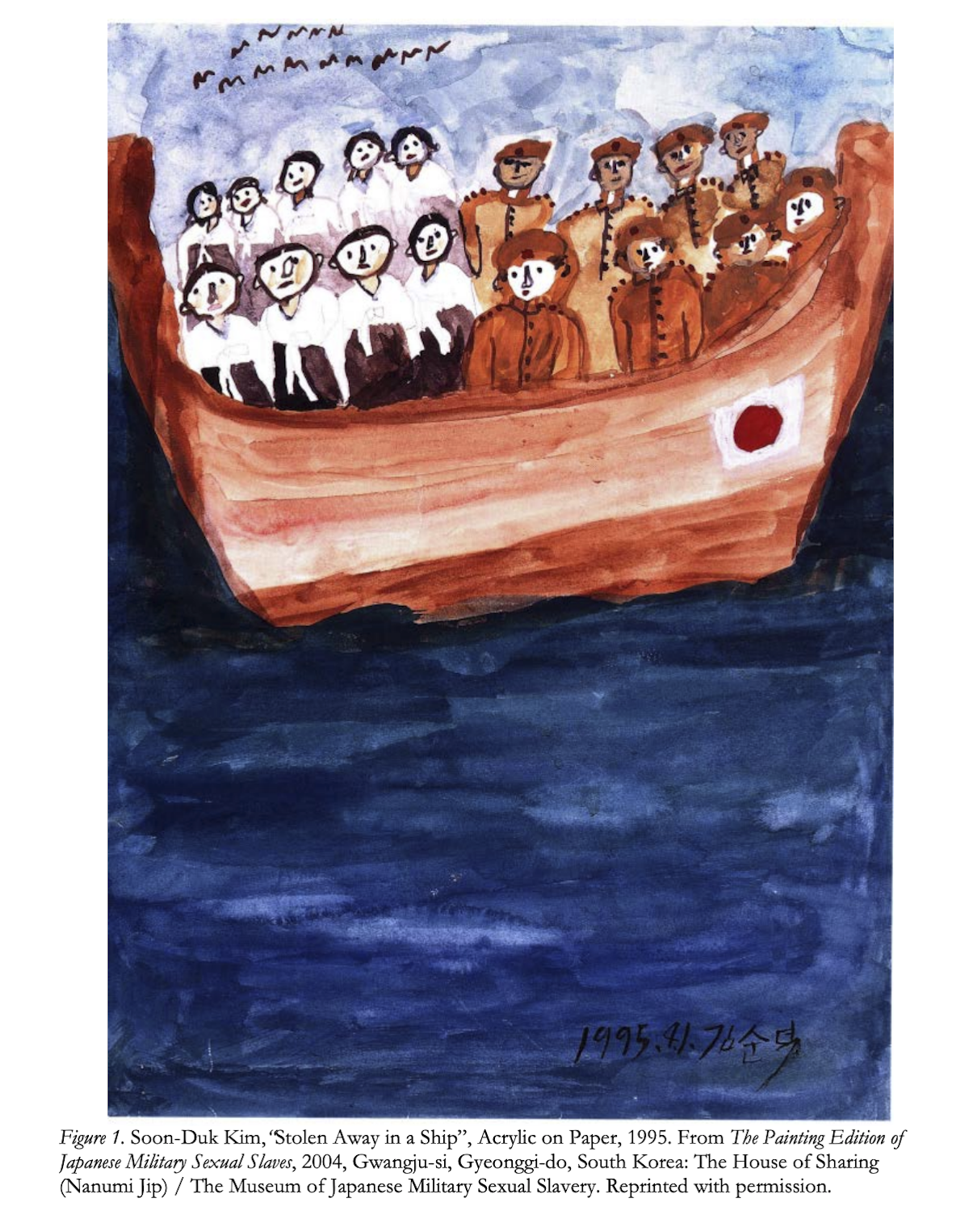

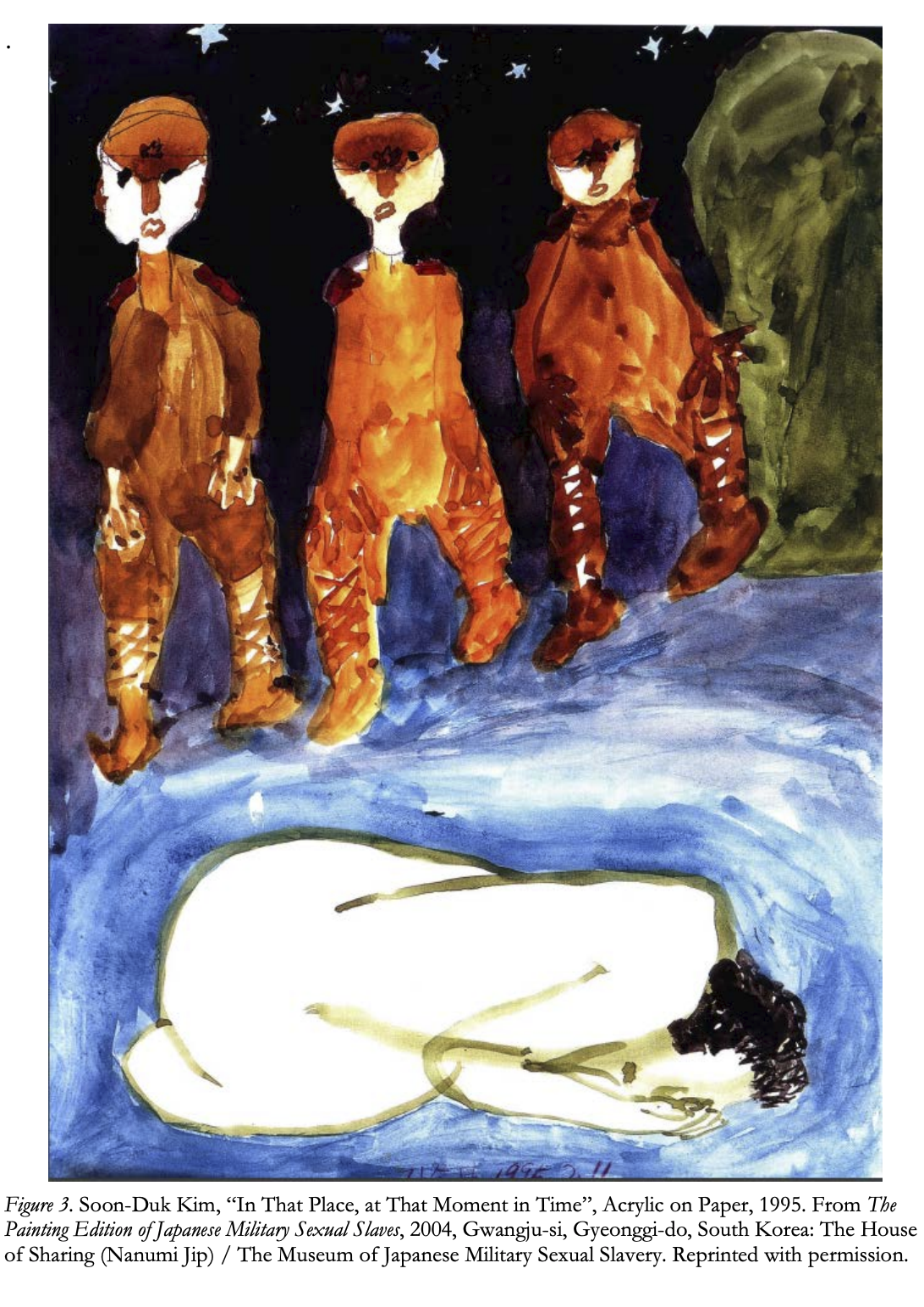

These demonstrations had begun on January 8, 1992, led by surviving “comfort women” – a euphemism for women who were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military during World War II. The survivors demanded an official apology, compensation, and recognition of the crimes committed against them. As their demands continued to be ignored, the statue was installed as a symbolic act. Initially, the survivors had only intended to set up a small memorial plaque, but the Japanese Embassy opposed even that. In response, a Korean artist couple designed the now-iconic statue, which was installed with the support of Korean civil society.

Designed by artists Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung, the Peace Statue depicts a young girl wearing traditional Korean attire, seated in quiet defiance, often barefoot, with a bird on her shoulder. It symbolizes not only the innocence lost but also the intergenerational trauma and the resilience of survivors. The chair next to the statue invites passersby to sit in solidarity.

A controversial 2015 agreement between the Japanese and South Korean government declared the “comfort women” issue to be “finally and irreversibly” resolved, without involving the survivors in the negotiations. Although Japan issued a formal apology and provided an estimated 8 Million Euros to establish a foundation in Korea called “Reconciliation and Healing,” many survivors rejected the funds. They criticized the agreement, particularly its condition that the original statue in Seoul be removed. Their core demands — such as building a memorial in Japan, including the issue in educational curricula, and fostering public awareness — were entirely excluded.

The installation of the statue in Berlin has been met with significant resistance, particularly from the Japanese government and local political figures, such as Kai Wegner, who have been influenced by diplomatic pressures. Despite legal challenges and threats of removal, activists remain committed to preserving Ari as a symbol of remembrance and resistance.

Columbia Law School

Center for Korean Legal Studies for educational purposes only

Jana: The Global Relevance of Ari

Jana emphasized that Ari represents not only the survivors of Japan’s wartime sexual violence but also all FLINTA* people affected by gender-based violence worldwide. She highlighted that the statue serves as a reminder of the systemic oppression women face in times of conflict and peace. The statue has also become a site of solidarity, uniting people affected by sexualized violence, racial injustice, and patriarchal structures. Jana stressed that the fight for justice extends beyond historical events; it is a contemporary struggle against ongoing violence and oppression.

Youngsook: Breaking the Silence

Youngsook, who is not only a member of Korea Verband but also “AG Trostfrauen”, reflected on how the issue of comfort women remained a taboo topic in Korea for decades. It wasn’t until the 1980s that survivors began to speak out, challenging the collective silence imposed by society. She recounted how Korean and Japanese women’s groups collaborated to expose and oppose Japan’s continued denial of these war crimes. Over time, the movement grew, leading to international conferences and broader recognition of these injustices. Youngsook’s account underscored the importance of intergenerational activism and the continuous effort required to combat historical amnesia.

Ngân: Political and Legal Demands

Ngân, a legal expert, outlined three major demands for justice to the German government and society:

- Recognition and reckoning with Germany’s and Japan’s colonial past – We demand that Germany comprehensively confront its colonial history and acknowledge its ongoing structural and institutional impact. This includes exposing Germany’s entanglements with Japan’s colonial history. Both countries shared imperialist ideologies in the 19th and 20th centuries and expanded their power at the expense of marginalized communities. The systematic violence against women in the so-called “comfort stations” must be recognized as part of this history and included in Germany’s culture of remembrance. Germany must stop deflecting its responsibility, whether in addressing its own crimes or in its international relations. The support of colonial and patriarchal structures must be questioned and ended.

- An end to the criminalization of activism – We demand that the German government protect activists who fight for social justice and against imperialist structures. Instead, we experience surveillance, obstruction, and the criminalization of such initiatives — especially when they are led by marginalized communities. This reveals how deeply racist and colonial structures are embedded in German institutions. The state must ensure that freedom of speech and assembly truly apply to everyone and actively oppose foreign influence, such as that from Japan, which undermines our work for Ari and our educational projects.

- Recognition that we are part of German society – We are tired of constantly having to prove that we belong to this society. The question of why Ari is here clearly shows how we, as racialized and migrant communities, are excluded. Such arguments rely on language rooted in immigration law that systematically marginalizes us. The district mayor’s call for “diversity” in public spaces ignores that true diversity means reflecting the society that actually exists in Berlin. We demand that our histories and voices finally be recognized as part of German society. Ari must stay — she is a symbol of our struggles, our history, and our belonging. Exclusion must end, and we must be acknowledged as equal citizens, not as people who have to continually justify their right to exist.Beyond Germany, the activists highlighted the need for broader systemic changes. Ngân argued that international law itself is rooted in colonial and patriarchal structures, benefiting powerful states while failing to protect the most vulnerable. Instead of merely introducing new laws, the legal system must be decolonized and restructured to ensure justice for all, particularly in the face of modern conflicts in Palestine, Ukraine, Lebanon, Syria, and Kongo.

The global fight against genocide, war, and patriarchal violence requires radical systemic change. Therefore, the action group ‘Comfort Women’ within Korea Verband specifically makes these following demands to the world:

The global fight against genocide, war, and patriarchal violence requires radical systemic change. Therefore, the action group ‘Comfort Women’ within Korea Verband specifically makes these following demands to the world:

- A Global Anti-Colonialism Law – States and corporations must be held accountable for neocolonial exploitation. This includes protecting land rights, resources, and cultural identities of Indigenous and marginalized peoples.

- Feminist Foreign Policy for Peace – War and violence disproportionately impact FLINTA* and children. A feminist foreign policy should prioritize preventive measures and the protection of the most affected populations rather than military escalation.

- Global Solidarity and Demilitarization – International cooperation should not be based on arms exports and military alliances but on promoting social justice, humanitarian aid, and economic equality.

- Reparative Justice – Countries that violate international law should not only face sanctions but also be obligated to provide reparations for their victims.

Ngân’s response to the following question “What international law should exist to protect people, especially women and children?” is as follows:

- A Comprehensive International Protection Law for Women and Children – This law must recognize all forms of violence against women and children—including gender-based violence, genocide, displacement, and structural discrimination—as crimes against humanity.

- A Binding Law Against Patriarchal Violence in War – Gender-based war crimes such as systematic rape or enslavement must be more strongly prosecuted, with mandatory accountability mechanisms for perpetrator states.

- An International Tribunal for Ecofeminist Justice – This tribunal would address cases of environmental destruction and its impact on marginalized communities (especially women and children), ensuring reparations are enforced.

Lastly, I was interested to hear what would need to happen on a legal level to prevent countries from violating international law so easily. Ngân explained as follows:

- Decolonizing International Legal Mechanisms – International law was developed at a time when colonial and patriarchal structures dominated, and it continues to reflect these power dynamics. This legal order was largely created by colonial states and men, benefiting those who designed it. A decolonization of international law is necessary: decision-making and enforcement processes must include feminist and decolonial perspectives to create a fairer foundation that treats all states and communities equally.

- Strengthening International Institutions – International organizations like the United Nations (UN) must be independent and capable of enforcing international laws. It must no longer be acceptable for powerful states to refuse to sign or ratify treaties while still violating international norms with impunity. A system must be established where all countries follow the same rules, without geopolitical interests undermining enforcement. International institutions must be reformed to be truly capable of implementing global standards fairly and consistently.

- Mandatory Accountability for States and Corporations – International courts must obligate states and corporations to be held accountable for human rights violations, war crimes, and environmental destruction. The current structures allow powerful countries and transnational corporations to escape responsibility. A legally binding system ensuring their accountability is essential for promoting global justice and effectively punishing crimes.

- A System of Global Feminist Accountability – Countries that systematically violate women’s rights and fail to protect children must be held accountable. A global feminist oversight system — through independent monitors and sanctions — could ensure that women and children are no longer the primary victims of violence and injustice in war and crisis situations. Such a system would not only strengthen international standards but also center the protection of the most vulnerable groups.

Date: C. 1945, Location: Okinawa, Japan. Image courtesy of Densho Digital Repository for educational purposes only

Despite the immense challenges, the activists remain hopeful. They find strength in community solidarity, the participation of younger generations, and the knowledge that every effort — no matter how small — contributes to a larger movement. As Jana noted, activism is not just about immediate results but about laying the foundation for future generations. Through Ari, the fight for justice continues, ensuring that the voices of the past and present are never forgotten.

_

To learn more about Korea Verband and the Peace Statue, please click here. Original artwork created by Katia Engell. For more articles about the Asian diasporic community, please click here.