Your aim to transform what we fear into love is very appealing. That’s what art…

Shamiran Istifan

We chatted with the Swiss-based visual artist about her work26 May 2020

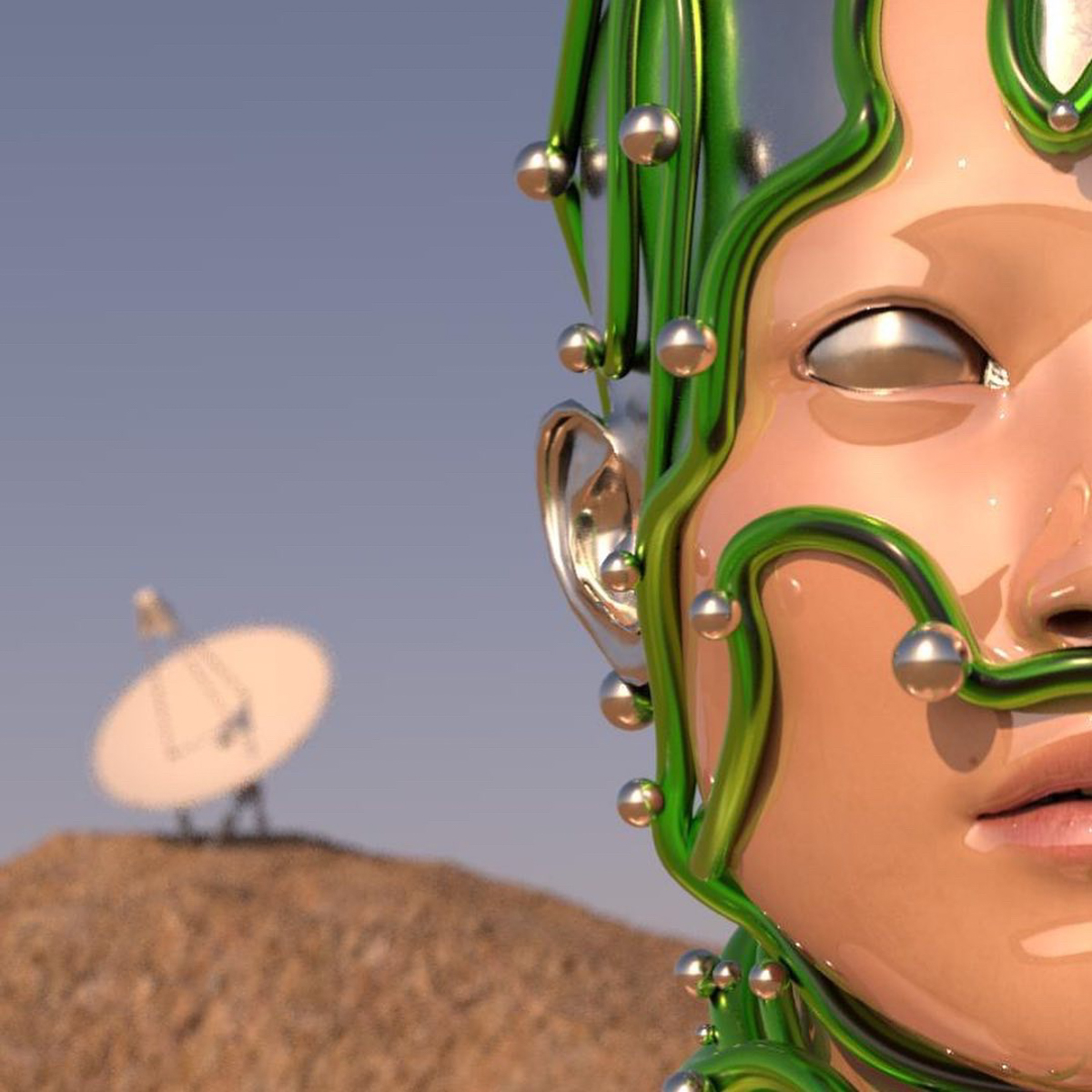

We sat down to chat with Shamiran Istifan (@kafirahm) a Swiss-based visual artist working with Middle Eastern symbolism and modern luxury kitsch, to chat about her work and her inspirations:

Hi Shamiran, lovely to speak to you today. You have a lot of unusual and beautiful visual elements in your art. Where do they come from?

Shamiran: Symbolism from daily life is something that speaks to me. I love that banal objects or visuals are – sometimes unconsciously – charged with meaning, even becoming sacred, defined by a society or culture that maybe didn’t even intend to define this thing. It simply comes from visual and emotional impressions of lived experience, and this is what inspires me.

The play between gentle and harsh, between individual roles, between political structures, religious meanings, and inner life can appear in many ways and shapes. The elements don’t represent only one thing, rather they display the reference and experience of the viewer with it. I still try to retain the original story/meaning of the elements I use in my work. I am happy when I get feedback from people who can relate to details and codes due to a common cultural background; it’s like having a common language for ourselves.

As we understand it, you didn’t plan to become an artist right away. What career did you plan to pursue originally and what made you choose the artistic path instead?

Shamiran: Many girls of my generation, from a traditional-cultural background, would understand if I told you that for a long time I didn’t have any other concrete future plan than to get married to someone from my community. I was even almost engaged by nineteen; I wanted to rush into marriage so badly until I realized that my personal path was more nuanced than switching from “someone’s daughter“ to “someone’s wife“ to “someone’s mother“.

Thankfully my parents cared a lot about our education as a foundation and when it came to studying, I wanted to take the fastest route to working life after studying for three years and chose to become a teacher. While I was studying I wasn’t very motivated because I naturally cared more about politics and about what was going on in the world, especially when coming from a cultural Assyrian enclave which has been politically active since forever. I was driven by the urge to share stories and when the Syrian War started and IS committed its crimes in Iraq, I got more opportunities to work at different media stations for research and translations.

The one I liked the most was research work for a political news magazine for Swiss TV. The last news station I worked for was frustrating in many ways and dictated how Syrian opinions on the Syrian war were portrayed. Imagine, people who weren’t personally affected [by the war] were telling affected people that they were crazy or wrong because they didn’t share the same political agenda.

Regarding the Syrian War, I experienced this “whitesplaining“ more than once. By some coincidence I applied to the Art University for Art Education with a friend and I casually participated in a show, which happened again and again. Each time I thought it was an exception but later I realised that I am an artist and that I love sharing stories through visual impressions. The freedom, the visualization, and the abstraction that art brings is the perfect shield of protection I need to share more and more stories.

What was it like not coming from an artistic sphere and how did this impact your navigation through the art world as an artist without “connections”? What worries did you have in the beginning and what were your breakthrough moments?

Shamiran: Sure, it’s easier when you are “born“ into connections or at least grew up with a natural knowledge about the academic world, the mentality, the social codes, or the creative scene.

“Impostor syndrome“ is such an omnipresent term but that’s the easiest way to describe the concerns I used to have. After I understood its political impact and that many people with similar backgrounds share this feeling, I realised that it’s just a subconscious belief pattern I had to unlearn, conditioned by social experience and unspoken laws – even in a “very leftist“ scene. I learned that even openly progressive ideologies in a scene can be a decorative coat of theory for the same old patriarchal and post-colonial structures in practical daily life. I am still learning to trust my experience over what is told to me; what I’ve experienced is that the ideology of equality should be less professionally performed and more practically applied.

I can’t speak of a special breakthrough moment; I still feel as I just started off. It’s a constant progress and I am feeling more comfortable with each release of work. As I said, it’s naturally easier if one has all possibilities, political carelessness, connections, and freedom given to them on a silver platter, but let’s not underestimate that a lack of [these things] can create more essential and philosophical stories to be told and also strengthen a person’s resilience – which I personally find more interesting.

We would love to talk to you about cultural appropriation and working class appropriation that is performed quite bluntly in the art sphere. And do you have any ideas about how people with different cultural and class backgrounds could communicate with more respect?

Shamiran: I would agree about it being often performed. I’d say that it’s not only the very simple cases of appropriation but also the ones where there are more layers to consider than the obvious ones (like appearance, financial status, or lifestyle).

If one comes from a wealthy family but chooses to be a starving artist, it’s a lifestyle [choice] and being poor by choice. Cultural appropriation is not just something that happens based on race but can also happen in other communities and subcultures when one does not have a truly lived experience in that community or subculture but speaks on behalf of that community or subculture.

I would also like to talk about deconstruction by way of taking away layers of appearance, name, and/or heritage. If the environment and household was white/swiss or swiss-passing by mentality, then I don’t feel like they can speak for a group of people that was born and grew up in the culture with its own value system, social codes, lingual aspect, and life choices.

I acknowledge the individual struggle and experience of each person, but I simply believe that if one is choosing to work with obvious labels and symbols of groups one isn’t really part of, then it should be with more awareness. There can also be various types of a working class – i.e. you can grow up in a working class where your parents have an interest in art and culture, are educated, read books, and encourage you to become what you want and you can also come from a background where there is really no connection to all of that. I don’t have any other concrete idea than trying to be at least aware of the layers of all this.

“Abundbashmayo” in Syriac letters written on a pillow. Translation: “Our Father in Heaven”

Your art references Middle Eastern folklore but then all the Louis Vuitton symbols come into play… What does this juxtaposition mean and does it have a political purpose? How do people perceive your sculptures?

Shamiran: I will try to explain some part of my take on using these things but I won’t go into what “luxury brand vs. satellite dish“ in society generally symbolises because my focus wasn’t on obvious dualism itself. About the Louis Vuitton part: It’s dedicated to my memory of the fake LV bags many girls and women from our community purchased back in the 00s years; also I used to own some with my older sister. Nowadays, being able to afford the original (authentic) LV bags are seen amongst the same community as “making it.” This can be a working class reality too.

You can see in this microcosm, how things can fundamentally change within a decade. In this case, for my parents’ generation, it [reality] meant less chances from the beginning, it means working hard and starting from zero, with little to almost no school education, no connections and no big space for self-fulfillment but doing it for others. There was less free choice and more of a survival mentality but it’s also more of a festive mentality (i.e. many family parties) when you have something to celebrate.

So, representative kitsch is necessary and we [my family, myself, and others from our community] have no interest in understatement or minimalism. I changed the LV logo itself into an arabic word through adding two dots, it became „baana“ which means “to sunder, to become evident through separation“ which is applied to a community that is a minority, not only here but also in the motherland and the importance of becoming grounded through sometimes strict traditions, symbols and rituals. The satellite dish is a classic (accidentally representative) symbol of migrant households; it’s somehow brutal but still has something cosmic [about it]. I am referring to a “membership by birth” – the center I made, the tissue box opening. The feedback people gave me on my work made me feel very grateful but honestly I don’t feel authorized to speak for the way they perceive it. I’m just trying to connect and tell [a story] through experience and my political take on this is that wisdom through experience is as precious as knowledge through education.

Haiwan means animal. Djinn means ghost. What other creatures do you cultivate in your artwork and what made you choose a Duvet as your canvas?

Shamiran: I found it interesting how we use our language to subconsciously separate a person from being human. In Arabic and Syriac-Aramaic it’s common to use animalism or lack of sanity (being possessed) in our everyday language to describe bad behaviour. On the other hand, there are saints and strong men in our culture who are treated like “superhumans“. It’s playing around with being socially passable or not and setting a standard for “human“. Many things also connected to the social idea of masculinity are either seen as animalistic (“he couldn’t control himself“) or as iconic (“he is a man of god“). There’s some non-representative space left in between those non-humans, human-possessors, and superhumans, and that’s shown through a duvet. There is a lot I can explain through a duvet (that I am currently using in different forms), but let’s say for this piece, it’s a soft energy carrying that firm madness.

We really liked your satellite dish-sculpture. Can you enlighten us about the way you produced it?

Shamiran: It’s pieces of aluminium put together like flower petals with a diameter of 1.80 meters. I used paint and many layers of epoxy as a coat with shimmering elements. In between those layers I embedded the LV-like pattern, piece by piece on the concave area. The center is a decorated opening of a former tissue box. And that opening contains a small traditional but altered jinn illustration that of a many-headed creature, coming out of a snake, coming out of a snake and looking up to an Assyrian star symbol that resembles one symbol from the LV pattern. Also, because of its large size and its concave form the satellite dish creates a reflection of sound waves which lets your words appear louder when you speak into it. I am so happy that you like it <3

_

Original artwork and photographs provided by Shamiran Istifan. Follow Shamiran on Instagram to keep up with her work. For more Art & Culture, click here.